Colonial American Holidays and Entertainment by Karen Helene Lizon, 1993.

This book explains how people living in Colonial America would entertain themselves and celebrate holidays. Both entertainment and holidays varied between time periods and geographical areas.

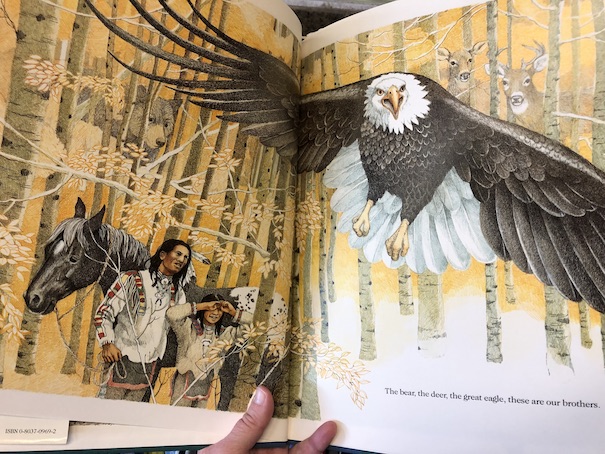

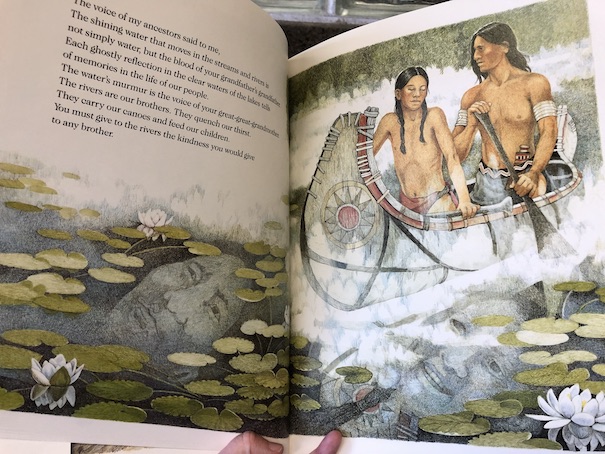

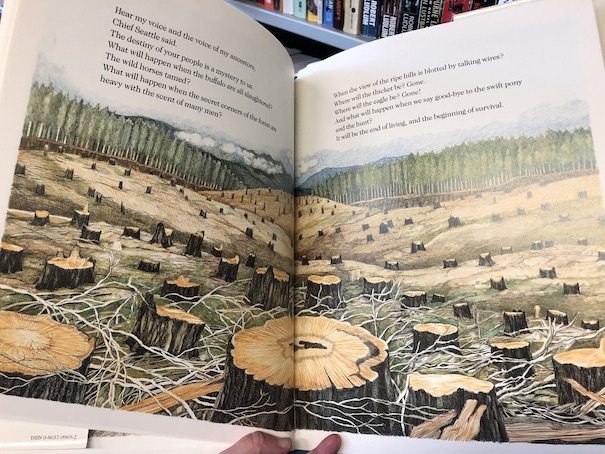

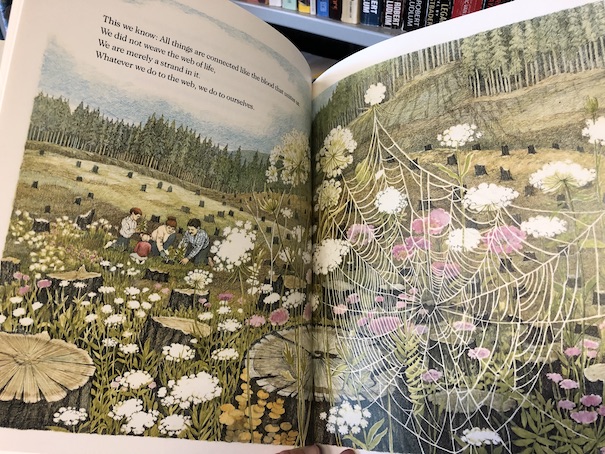

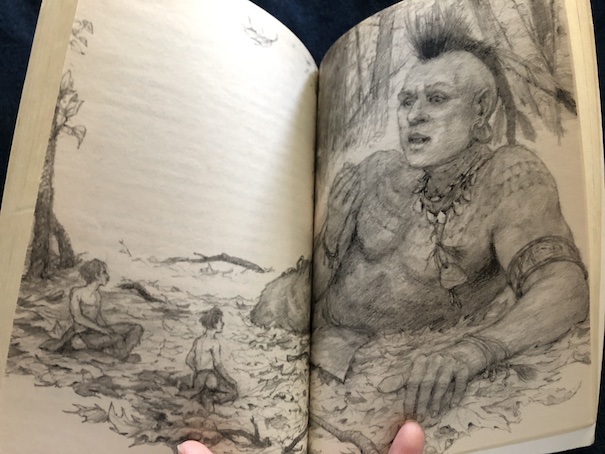

In the early days of European colonies in North America, life was hard. People were occupied with daily survival and the establishment of their communities. As their communities expanded and became more settled, they were gradually able to have more leisure time. The book begins with a general history of the American colonies, briefly explaining the range of countries the early colonists came from, the effect their arrival had on Native Americans, and the role that indentured servants played in society and the adoption of slavery as a means of obtaining workers.

I was glad that they brought up the point about indentured servitude and slavery because I remember discussing it in my college history courses. Indentured servants were people who would agree to work for someone for a period of time in return for having that person pay for their passage to the colonies. There was a benefit for both sides in indentured servitude. For the indentured servants, they used their labor as a means to pay for transportation to the colonies that they could not have afforded by themselves, and once they had worked for the required period, they would be free to establish themselves independently in the colonies. For those who paid for the indentured servants, they would have guaranteed workers for the period of the indenture. However, plantation owners and other employers soon realized that they were not finding as many indentured servants as they wanted, and they didn’t like losing their labor force when their terms of indenture ended the workers left their employ. Therefore, they began to turn to slavery as a means of gaining a steady stream of workers who could not say no to them, no matter what the working conditions were like, and could never leave. Slavery wasn’t so much about race in the beginning as economics and employers who wanted cheap, permanent labor and didn’t care how they got it or what it would mean to the people they bought. But, I have other books that say more about what that led to. This book is mostly about lighter subjects, but it does acknowledge the serious aspects of American history and also makes the point that these completely unwilling immigrants also became a part of American society and, like other groups who came to America willingly, also brought traditions and folklore of their own that would gradually become part of American society, entertainment, and celebrations.

During the Colonial period, celebrations and entertainment varied throughout the regions of the American colonies, depending on the mixture of colonists living there and the holidays and traditions they brought with them from their homelands. Some of their holidays were ones that we still celebrate today, while others have fallen out of favor.

The book is divided into chapters based on different aspects of entertainment, and I’ve given a brief description of each, although all of these sections have more detail than I’ve provided. I particularly recommend reading the book if you would like more information about Native American entertainment or the lives of slaves because there is more information about these topics than I’ve described.

The chapters are:

Winter and Spring Holidays

Christmas seems like one of the most obvious holidays for colonists to celebrate, but it wasn’t so straight-forward. First, not all of the colonists were Christian (there were some Jewish people in parts of the colonies, and they celebrated Hanukkah in the winter), and even among those who were Christian, not all actually celebrated Christmas. The Puritans, who wanted to separate themselves as much as possible from traditions which they thought were not part of pure Christianity, did not celebrate Christmas. In fact, they didn’t celebrate many holidays or special days at all. Apart from the Sabbath, they only had a Day of Humiliation and Fasting and a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise, and those were not regularly scheduled events to be held on any specific date; they were only declared when it seemed that circumstances called for them. A Day of Humiliation and Fasting would happen at a time when things were going badly and the community was suffering, and the Puritans would use that day for prayer, reflection on their sins, and repentance. A Day of Thanksgiving and Praise would happen when the community was prosperous and felt blessed, and it was a time of prayer and feasting.

Also, among the Christians who did celebrate Christmas, not all of them celebrated it on the same day, and different groups had different customs for Christmas, depending on where they were originally from. People from Sweden celebrated St. Lucia Day on December 13th, and people from the Netherlands celebrated Sinterklaas Eve and Day on December 5th and 6th. It was also common for Christmas celebrations to continue through the Twelfth Night from Christmas itself, January 6th, also call Epiphany (the day that the Wise Men visited Jesus).

Easter is a common Spring holiday in modern times, but in Colonial times, it wasn’t so widely or elaborately celebrated. Colonial children were not told stories about an “Easter Bunny” delivering eggs or candy, although colonists from the Netherlands did decorate eggs with natural dyes and scratched designs into the shells.

A spring holiday that many of the colonists celebrated (but not the Puritans) but few people celebrate in modern America was May Day. On May 1st, people would gather flowers and dance around a Maypole.

Summer and Fall Holidays

The Fourth of July is the essential summer holiday of modern America, but it didn’t exist until the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Many people’s lives centered around agriculture in colonial times, so fall was harvest time for them. Some colonists (although, not all, and definitely not the Puritans) also celebrated Halloween. The holiday was particularly celebrated in communities where there were people of Irish descent. (This book doesn’t say so, but at this time, it was particularly a Catholic holiday, the eve before All Saints’ Day on November 1st, although some other Christians celebrated it, too. Some Protestant groups, especially the Puritans, shunned the holiday as being too Catholic. I covered the general history of Halloween in more detail on my site of Halloween Ideas, including how Halloween became a secular American holiday.)

In some areas, colonists celebrated an anti-Catholic holiday called Pope’s Day on the 5th of November, where they would burn effigies of the pope. This was an older holiday than the English Guy Fawkes Day, celebrated on the same day, and that holiday was also celebrated in the parts of the colonies with English influence.

Of course, both colonists and Native Americans had harvest celebrations in the fall, including the periodic Thanksgiving feasts that led to our modern Thanksgiving holiday.

Sports and Recreation

Much of the lives of the early colonists focused on basic survival and the establishment of their new communities. (The book explains some of the ways Native Americans helped the early colonists to survive and adapt to their new environment and to unfamiliar foods.) There was always work to be done, and even young children had to help with daily chores. Still, they found ways to enjoy themselves. Hunting expeditions were a kind of adventure, and children were often assigned the fun chore of picking berries.

Then they had leisure time, they would enjoy games like shovelboard (like shuffleboard but played on long tables), ninepins or bowling (done at first outside on the village green), and billiards (some of the more prosperous families had their own billiard tables). In the 17th century, ninepins was the primary form of bowling with pins instead of our modern ten-pin games. Ninepins, also called Skittle, was the game that Rip Van Winkle played in the story set during this time by Washington Irving. When they talked about just “bowling”, they didn’t use pins at all, instead rolling a ball toward a designated mark on the ground. Boys played stick-and-ball types of games, like stool ball. Even Colonial women enjoyed a game of stool ball. Other games and sports Colonial people enjoyed include quoits (a ring toss game), tennis, battledores, swimming, canoe races, foot races, wrestling, and horse races. Wealthy families even engaged in fencing and (believe it or not) jousting.

During the winter, children built snow forts and had snowball fights and went sledding. Both adults and children went ice skating.

Games and Toys

Many Colonial children’s toys were homemade. It was common for boys to whittle wooden toys for themselves such as whistles and windmills. Boys also had toy guns and bows and arrows. Colonial children liked to roll hoops, either homemade wooden ones or metal hoops from an old barrel. They rolled the hoops upright along the ground using a stick to keep them going, and the object was to go as fast as possible without loosing control of the hoop or having it fall. (They did not use hoops as hula hoops.) Native Americans also played with hoops, and they liked to make it a challenge to throw a spear through a moving hoop. In modern times, jump rope is often considered a girl’s game, but in Colonial times, it was more popular with boys, and they had their own jump rope rhymes. Colonial children also played with spinning tops, marbles (Native Americans had their own traditional marble games as well), jackstones (a precursor to modern Jacks), kites, toy boats, balls, and swings. Girls had dolls (usually homemade and sometimes corn husk dolls at harvest time and paper dolls they made themselves), and some of the more fortunate girls had doll cradles and dollhouses with furniture. Many homemade toys were actually very durable and were passed on through families for generations.

Children also played many games that are still popular on modern playgrounds, including various forms of tag, counting-out rhymes (like the kind modern children use to choose who is going to be “it” in a game), hide and seek, blindman’s buff, leapfrog, cat’s cradle, and hopscotch (which they called “scotch hoppers”). Sometimes, they played board games, like Checkers, Chess, Backgammon, and Nine Men’s Morris.

People throughout the colonies played various types of dice, domino, and card games, some of which were gambling games. Gambling rules and taboos differed throughout the colonies, but in some areas, even children were allowed to gamble.

Social Amusements

A primary form of entertainment in Colonial times was visiting friends and neighbors, and they developed a form of social etiquette around visiting. Some people had specific days when they were expected at friends’ homes, and people often left calling cards to show that they had visited. (Since people couldn’t phone someone to say that they were coming to visit, they either had to prearrange the visit ahead of time to ensure that they were expected or leave a calling card if the person they were visiting happened to not be home, so they would know that a friend stopped by and wanted to talk to them.) Women who lived in towns held tea parties, and pioneer families had picnics that included fishing and berry-picking.

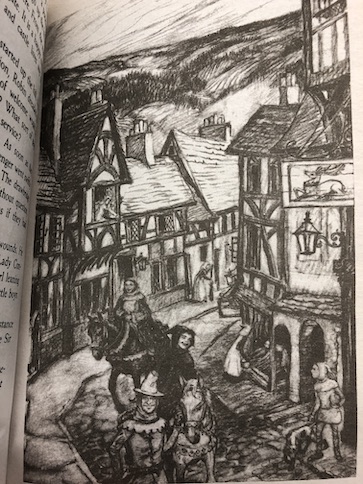

There were seasonal fairs in spring and fall with entertainment like juggling, puppet shows, tightrope walking, fortune-telling, music, exotic animal shows, and various types of contests. The fairs were also part business and involved trading and selling various types of products.

Colonists’ social lives also included political and religious community meetings. Towns would hold meetings to discuss town business and issues of local concern. Election days for public offices often had an air of public celebration as people watched public speeches and debates and booths sold good things to eat to the spectators. Citizens were welcome to attend criminal court trials and witness public punishments designed to humiliate offenders. Communities held market days when farmers, businessmen, and even Native Americans could gather to buy, sell, and trade products.

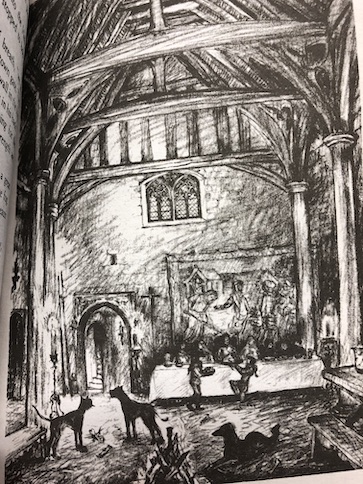

Church attendance and activities varied by denomination and geographical location. In some areas, church attendance was mandatory, and people would not engage in any other business or activity on Sunday. In areas where neighbors didn’t live close to each other, church was one of their main opportunities to see each other, and it was common for families to meet and share meals after church or for young men to visit with girls they liked.

Taverns, inns, and coffee houses also became important community meeting places. They could be uses as places for community meetings, political discussions, arranging business deals, distributing news and mail, and (as a later chapter explains) sometimes theatrical performances.

Entertainment and Pastimes

Because Colonial life was often hard and full of work, learning how to entertain yourself at home and keep yourself amused while performing chores were important. Work and entertainment often went hand-in-hand, and social occasions were often accompanied by chores and activities to keep the hands busy. Children started learning useful skills early in life. By the age of five years old, girls were able to sew. They also learned knitting, weaving, and embroidery, showing off the range and variety of stitches they knew in hand-sewn samplers. (Originally, samplers were meant to be exactly that – samples of the variety of sewing stitches a girl knew how to do. They were meant to be a demonstration of learning and accomplishment. They were very different from modern samplers that only contain one stitch – cross stitch.) Girls as well as boys knew how to whittle wood, and it was common for children to trade things they had made themselves for other things they wanted. Families had gardens where they grew vegetables, herbs, and flowers that the family could enjoy, and some women developed side businesses selling vegetable and flower seeds from the family garden.

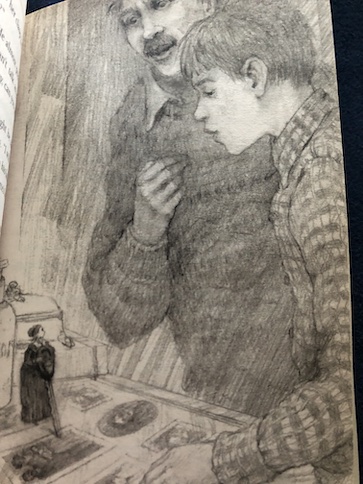

While not everyone knew how to read, many people did, and they would read books like the Bible, works by Shakespeare, and books of poetry. Some people even wrote poetry for fun. Benjamin Franklin opened the first lending library in Philadelphia in 1731. Families often provided their own entertainment in the evening, telling stories and folktales around the fire.

Communities also had musical performances and public dances. Different colonies had different customs regarding dancing, with some communities making it taboo for men and women to dance together. Wealthy plantation owners held fancy formal balls. Music was a common part of children’s education because people who knew how to sing or play an instrument could help entertain their families at home. Some people simply used improvised instruments made out of various objects that they happened to have on hand, like a comb covered in paper, spoons, or tin kettles.

Early American Observances

Aside from the holidays described earlier, there were other special occasions that communities celebrated. Families gathered to celebrate births, baptisms, and weddings. Even funerals, while being a time of mourning, were also social gatherings. Sometimes, wealthy families would give little gifts to those who attended family funerals.

Some children had birthday parties. In the early days of the colonies, people were too occupied with the business of survival to bother much with remembering birthdays, but as communities became more settled and stable, birthdays were increasingly celebrated, especially among the more prosperous families. Sometimes, children were excused from chores on their birthday, and they were often given practical gifts.

Native American groups also had their own seasonal festivals and ceremonies of thanksgiving that varied among tribes. These seasonal festivals marked times for planting or harvesting crops or moving to seasonal quarters. They would also have ceremonies to mark special life events, like testing boys to see if they were ready to be men in their communities.

Working Bees

As I said, work and fun often went hand-in-hand in Colonial America, and sometimes, the colonists would hold special working parties called “bees.” When people got together in big groups to take care of major chores, the work got done faster, and they could have fun talking and visiting with each other while they did it. When they finished with whatever task they set out to do, they would finish the event with food, games, and other fun activities.

At harvest time, they would hold harvest parties to harvest food and prepare it for storage. At apple bees (the parties, not the restaurant), people would peel and core apples and make apple-based foods, like cider and applesauce. At husking bees, they would husk corn. There was also an element of flirting to husking bees because, if a man found an ear of red corn, he was allowed to kiss a woman sitting near him.

At other times of the year, they would hold different types of bees for specific tasks or crafts. “Raising days” were when people got together to build a new building, like a house, barn, or public building, like a schoolhouse. Women held quilting bees and knitting bees. Children today still compete in spelling bees, just like colonial children did. “Sparking bees” were kind of like colonial singles meetups. Single young people in the community would come to the bee to meet each other, and if they found someone who “sparked” their interest, they could begin a formal courtship with that person.

Games, Goodies, Gifts

The final chapter of the book has words for the counting-out rhyme “Intry, Mintry” and the rules for the tag game Fox and Geese and the spinning top game Chipstones. There are recipes for Maple Sugar-on-Snow, Furmenty, Speculaas (a Dutch Christmas cookie), and Raspberry Flummery (a sweet drink). There are also instructions for making a pomander ball.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.