The Enchanted Castle by E. Nesbit, 1907.

Boarding School Break

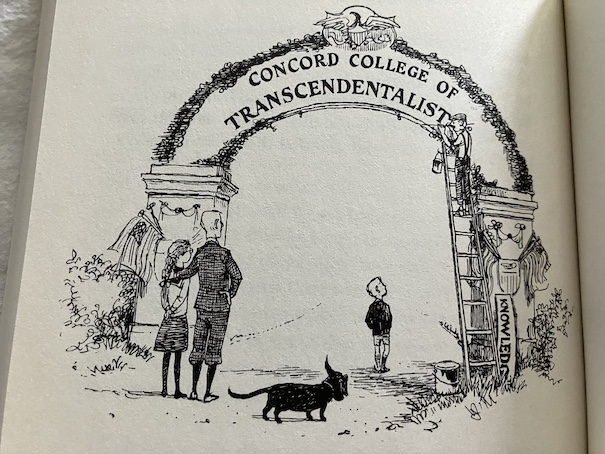

Two brothers and two sisters spend most of their time at boarding schools. The boys go to a school for boys, and the girls go to schools for girls, so the only times when they are together are when they are home for school holidays or visiting at the house of a kind, single lady who lives near to their schools. Although the children’s parents are grateful for their single friend for hosting the children as guests from time to time, the children find it difficult to play at her house because everything is so neat and proper, and they don’t feel quite at home. Then, during one school break, one of the sisters, the one who makes it home first, comes down with measles. With their sister sick, the other siblings can’t go home, which is a great disappointment, and their parents have to make other arrangements for them. When the children tell their parents that they don’t want to visit the single lady for the entire school holiday, the parents arrange for the boys, Gerald and James (called Jerry and Jimmy), to board at their sister Kathleen’s school. It will be fine for them to be there because Kathleen (called Cathy) is the only student remaining at the school during the holiday, and there will only be one teacher there to supervise them, the school’s French teacher.

This arrangement suits them better than going to the single lady’s house, although they think that they ought to find something special to do during the school holiday. Kathleen suggests that they write a book, but the boys aren’t thrilled by the idea. They would rather do something outdoors, like playing bandits. However, they are a little concerned about the French teacher’s supervision. Fortunately, Gerald is good at charming grownups, when he wants to. Through a combination of flattery and small, thoughtful favors to the teacher, he gets on her good side, and he manages to convince her that he and his siblings would like to have some time to themselves to play and explore outside, maybe in the woods. The French teacher understands that what they really want is some freedom from supervision, but she agrees to give them some time to themselves.

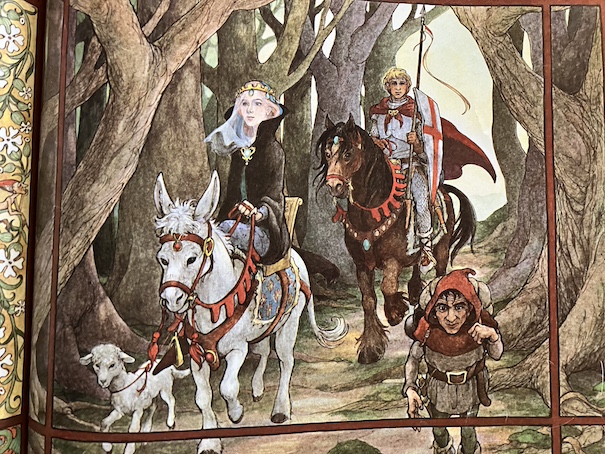

The children don’t actually know if there are any woods in the area, but they decide to do some exploring and see if they can find an adventure of some kind. They end up getting lost during their exploring, but they find it exciting. When they sit down to rest, they find a cave and decide to explore it. The cave turns out to be a tunnel that leads them to a beautiful garden with a lake with a decorative waterfall and swans. The children imagine that it’s the garden of a magical castle. Going a little further, they find a thimble with a crown on it and a thread tied to it. It looks like the kind of thimble that might belong to a princess.

Meeting the “Princess”

When they follow the thread, they find a young girl in a beautiful dress who looks like she might be a princess. She looks like she’s asleep, so she looks like an enchanted princess or Sleeping Beauty. Jimmy doesn’t really believe that she’s a princess, but the others aren’t so sure, and anyway, it makes a fun game to pretend that she is. Since Jerry is the eldest of the children, Cathy thinks that Jerry should kiss her to wake her up. Jerry refuses, so Cathy says Jimmy should do it. Although Jimmy is sure that she’s really just an ordinary girl dressed like a princess, he says he’ll kiss her to prove he’s braver than Jerry and that he should be the leader for the rest of the day.

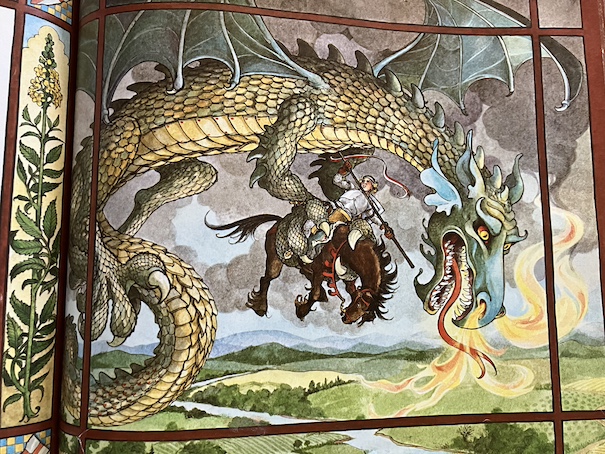

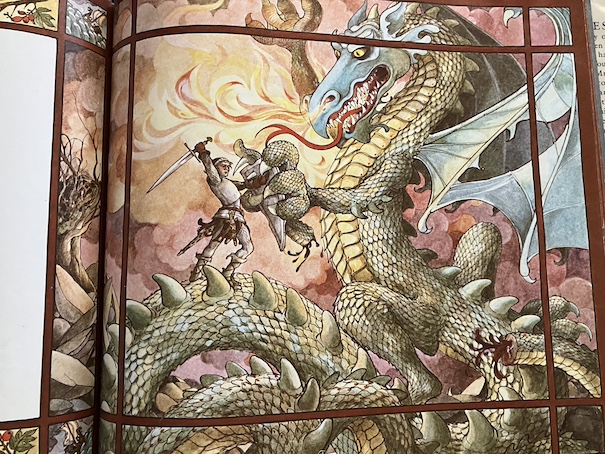

When Jimmy kisses the girl’s cheek, she opens her eyes and says that she has been asleep for 100 years. She insists that she’s a real princess and asks them how they got past the dragons. Jimmy still doubts that, even though she shows them a mark where she pricked herself on a spindle, just like in the Sleeping Beauty story. She invites them to come back to the castle and see her beautiful things. The children say that they are hungry, so they go with her go get something to eat.

When they get to the “castle”, the princess brings them bread and cheese to eat with some water. This seem depressingly ordinary, and the princess apologizes, saying that was all she could find. However, she claims that the food in the castle is magical, so it can be whatever they want. The children imagine that it’s roast chicken and roast beef, but all they get is bread and cheese. Cathy doesn’t want to admit at first that it’s just bread and cheese because (like with the Emperor’s New Clothes), there is an implication that there is something wrong with her if the magic doesn’t work for her. Jimmy isn’t discouraged by that, so he asks the princess if it’s a game, but the princess denies it, insisting that the food is magical.

Then, the princess takes the children to a hidden door behind a tapestry. The room inside has paneled walls and blue ceiling with stars painted on it. The princess calls it her “treasure chamber”, but the room is completely empty. The princess acts surprised when the children say that they can’t see any treasure, and they refuse to believe it’s because they’re magical or invisible. The princess has the children close their eyes while she says some magic words. When they open their eyes, suddenly, there are shelves with jeweled objects on them. The children have no idea how the princess accomplished this trick, so they start to believe that maybe she can do magic.

The Invisibility Ring

The princess suggests that they all put on some of the jewels and be princes and princesses, too. It’s amusing for a while, but the boys start getting tired of dressing up, and they’re still a little skeptical about who the princess is. They suggest that they go play outside, but the princess insists that she’s actually grown up and doesn’t play children’s games, and she has the others help her put all the treasures back in their proper places. She tells the children that various pieces of jewelry have magical property. Jimmy asks her if that’s really true or if she’s kidding, but the princess insists that it’s true. Jimmy asks her to demonstrate how the magic works. The princess says that she will try on the magic ring that makes her invisible, but only if everyone closes their eyes and counts first.

When the children open their eyes, all of the shelves of jewels are gone and so is the princess. Jimmy says that it’s obvious that the princess just went out the door of the room. When they close their eyes and count again, Jimmy keeps his eyes open and sees the princess hiding behind a secret panel. When he tells the others, the princess says that he cheated. The weird thing is, even though they hear the princess say that he cheated, they still don’t see her. They tell her to stop hiding and come out, but she says that she already has. She says that if they want to pretend like they can’t see her, that’s fine, but the children seriously can’t see her. When the princess realizes that they’re serious that she’s actually invisible, the princess suddenly gets scared. She tries to shake the boys and get them to say that she’s not invisible, and Jerry catches hold of her, still unable to see her. She tells them that it’s time for them to go because she’s tired of playing with them.

Jerry makes the princess look in a mirror to prove that she’s invisible, and the princess gets very upset. Cathy sensibly tells her to just take the ring off, but the princess says it’s stuck. She admits that the whole thing, up to this point, was just a game of pretend. She says that the treasure shelves were hidden behind some paneling, and she just moved it with a hidden spring. She never expected that any of it was actually magical. The truth is that the girl’s aunt works at the house as a housekeeper and that her name is Mabel. She was just playing at being an enchanted princess because the rest of the household is away at the fair, and she happened to hear the other children coming through the hedge maze, so she roped them into her game.

Since one of the objects that Mabel claimed was magical was a buckle that would undo magical spells, Cathy suggests that she try the buckle. Mabel says that’s no good because she only made up that it was magical, but Cathy points out that she also made up the part about the ring being magical, and it turned out to be true, so she might as well try the buckle. Mabel would, but they accidentally locked the key inside the room and can’t get in now.

The children sit down to think about the situation. Since they can’t think what to do, the other children think maybe they should leave and go get their tea, but Mabel insists that they can’t just leave her invisible like this. Instead, she suggests that she go with them to tea and leave her her aunt a note. While they have tea, maybe they can think of something else to help Mabel. In her note, Mabel says that she’s been adopted by a lady in a motorcar and is going away to sea. The others say that’s lying, but Mabel says that it’s fancy instead of lying and that her aunt wouldn’t believe her if she said that she was invisible.

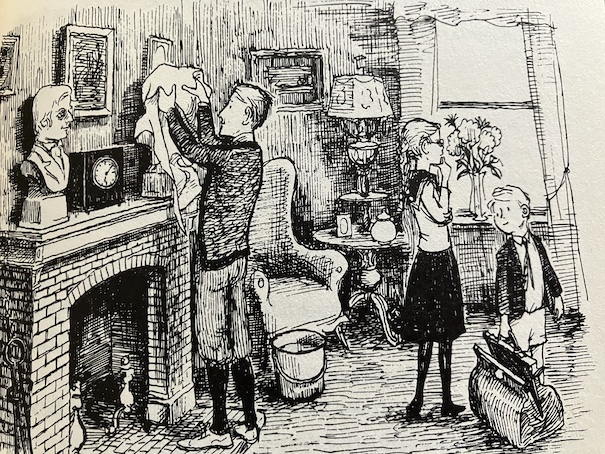

When they return to Kathleen’s school, they have tea and supper. They let Mabel have one of the three plates laid out for them, and Jerry and Cathy share one between them. Fortunately, the French teacher isn’t eating with them and doesn’t see an invisible person eating, but the children don’t know how they’re going to handle breakfast the next morning. They say that Mabel can stay the night with them, sharing Cathy’s bed and borrowing a nightgown. Mabel says that she can get some of her own clothes from the house tomorrow because no one will be able to see her and that she’s starting to see some possibilities for being invisible.

In the morning, the maid who comes to wake Kathleen sees Mabel’s discarded princess dress on the floor and asks Kathleen where it came from. Kathleen makes an excuse that it’s for playacting, which means that she and her brothers will have to figure out some kind of play to put on with it. Mabel thinks that acting sounds exciting, but Kathleen reminds her that she’s still invisible, so no one can see her perform anything.

The children feel bad about Mabel’s lies in the note to her aunt, and they insist that they should go and tell her the truth. Mabel doesn’t think this is a good idea because her aunt won’t believe her, but she reluctantly agrees. When they try to talk to her, the aunt doesn’t really want to listen to them, thinking that it’s just another one of Mabel’s pranks. She says that maybe Mabel was changed at birth and that her rich relatives have finally claimed her. They try to tell her that Mabel is with them, only invisible, and the aunt tells them not to lie to her. They ask about Mabel’s parents, and the aunt says that she’s an orphan. The children think that Mabel’s aunt is crazy because she doesn’t seem concerned about her and doesn’t want to hear anything they have to say, but Mabel says that she thought that her aunt might act that way because she spends so much time reading novels and can imagine anything.

In the meantime, Mabel has had some thoughts about what she can do. She says that she might be able to continue living in the house where her aunt works because the place is supposed to be haunted, so she can play ghost herself. However, the others think that she should stay with them. They just need a way to get some money to buy extra food for her.

Sine the fair is still going on, Mabel suggests that Jerry put on a magic show at the fair to get some money. The others say that Jerry doesn’t know any magic tricks, but Mable points out that it doesn’t matter when he has an invisible friend who can move things around, unseen, and make things disappear. Jerry dresses up as a conjurer from India (in a way that would be considered equal parts cheesy and offensive by modern standards because it involves black face), and he puts on the magic show with Mabel’s help. It’s incredibly successful, and toward the end of it, Mabel feels the ring coming loose. She takes it off and gives it to Jerry, who ends the act by vanishing himself.

Jerry’s and Eliza’s Invisibility

Now, Mabel is visible again, and it seems like they’ve solved their problem, but now, they have a new one. The ring is now stuck on Jerry’s finger, and he is the one who’s stuck being invisible. Although Mabel can now go home, she insists on staying with the other children and taking part in their next invisible adventure.

Jimmy says that, if he was invisible, he would turn burglar. The girls point out that would be unethical, so Jerry decides that he will be a detective. There are advantages to a detective being invisible. Then, Mabel remembers that the treasure room is still locked from the inside, and they have to do something about it. Jerry says that, as an invisible person, he can sneak in easily enough through a window. When he does this, he ends up foiling a robbery by actual burglars, although he also ends up letting them escape from the police because he knows that conditions in prisons are horrible and can’t bring himself to send anyone there.

After his adventure, the ring comes loose from his finger while he’s in bed, and the maid at the school, Eliza, finds it and decides to “borrow” it for an outing with her fiance. When her fiance can hear Eliza’s voice but not see her, he thinks that he’s taken some kind of strange turn or fit, possibly because he’s been in the sun too long. The children convince him to go home and lie down while they deal with Eliza. They take Eliza on a little adventure of her own because they’re beginning to see that the ring doesn’t come off someone’s finger until its purpose is fulfilled. Afterward, they manage to convince Eliza that it was all a strange dream that she had because she felt guilty about taking the ring without permission. The children also think that the ring’s power might be diminishing and could be completely spent because it seems like its effect has been lasting shorter and shorter amounts of time every time it’s used. However, this is really just the beginning of the ring’s magic, and it can do much more than they think it can.

The Living Dummies

At this point, they feel a little guilty that they haven’t spent much time with the French teacher, who is supposed to be looking after them, so the buy her some flowers. She is pleased with the gift, and they have a little party with Mabel as their guest. They find out that the French teacher has artistic abilities, although she rarely has time to draw these days because she’s so busy teaching. Mabel also tells them more about the man who owns the house where her aunt works. Although the house is grand, the man who owns it doesn’t really have enough money to support it and live there full time with a full staff because his uncle wrote him out of his will for falling in love with a girl he didn’t approve of. It’s sad because he also never married the girl because she was sent away to a convent, and although he did try to find her, he never did. Mabel, whose knowledge of convents comes from the scandalous gothic novels that she and her aunt read (much like the kind the main character reads in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey), speculates that the girl might be bricked up in a wall by now because that’s the kind of wicked thing that happens in books. The French teacher tells her that real convents aren’t like that and that the women who live there are good and take care of girls without parents, although they can also be strict, and the girls aren’t allowed to leave. She says it in a way that implies that she was one of those girls raised in a convent.

Since the children had claimed earlier that they were going to put on a show of some kind with the princess outfit, they decide to go ahead and perform for the French teacher and Eliza. To fill out the audience for their performance, they make a bunch of stuffed dummies, which the French teacher finds amusing. The children use the ring as a prop in their play, although none of them put it on, and Kathleen wishes that the dummies were alive so they could have better applause from the audience. To the children’s amazement and the French teacher’s and Eliza’s terror, the dummies (which the children think of as “Ugly-Wugglies”) do come to life and start clapping. In a panic, the children debate what to do. Jerry realizes that the ring is actually a wishing ring and is responding to the children’s wishes, so he wishes on the ring that the dummies were not alive, to undo Kathleen’s wish, but it doesn’t work.

To Jerry’s surprise, the dummies begin speaking to him, although their speech isn’t clear because they don’t really have proper mouths. They ask him for a recommendation to a good hotel or suitable lodgings. The dummies don’t seem to know what they are, and they are behaving like respectable, aristocratic people. Jerry tells them that he can show them to some lodgings, if they will wait for him a little. He makes some excuses to give himself time to reassure the French teacher and Eliza that the effect with the dummies was just a trick pulled by the children with string, and he recruits Mabel to help him find a place for the dummies. He does this in an insulting and condescending way, and Mabel tells him off for that, but she agrees to help him. They decide to hide the dummies somewhere on the grounds of the big house where Mabel and her aunt live, thinking that the magic will wear off eventually and that the dummies will turn into dummies again by morning. The dummies turn nasty when Jerry and Mabel try to shut them away, and they are helped by a strange man.

The strange man demands an explanation from the children about the angry people they’ve shut away, but the children don’t want to explain. The man says, if they won’t tell him what’s going on, he’ll simply have to let the people out and ask them, but the children are afraid of what the dummies will do if they’re released. The man assumes that the imprisoned people are other children and this is all some children’s game, so Jerry and Mabel decide that they have to tell him the truth, even though they know it all sounds crazy. They can tell that the man doesn’t really believe him. The man thinks maybe Jerry has a fever or something, and he says that he’ll see the children home. Jerry can tell that the man plans to open the door after the children are gone, and he warns him not to do that. He insists that the man wait until tomorrow to open that door and to wait for them to meet him to see it opened because, by then, they’re sure that the dummies will just be dummies again. The man reluctantly agrees.

When the children arrive the next day, they discover that the man didn’t wait for them to open the door, and he is now lying unconscious and injured, apparently attacked by the dummies. The dummies are gone except for the most respectable dummy, who seems concerned about the unfortunate man on the ground. Mabel runs for smelling salts to revive the unconscious man, and Jerry looks around to see where the other dummies are. They find that the other dummies have turned back into piles of old clothes, and only the one living dummy is left. He seems to be becoming far more real. The children revive the unconscious man, who turns out to be the new bailiff. The bailiff assumes that the strange visions he had were because he was injured accidentally. After the children are sure that he’s all right and send him on his way, they try to figure out what to do with the remaining living dummy.

The remaining dummy seems to have developed a life of his own and is quite a wealthy man, although the children aren’t sure that this will last because the ring’s magic never seems to last very long. Jimmy says that he wishes he was wealthy, and the other children are horrified to see him age quickly, turning into an elderly, wealthy man. Jimmy doesn’t seem to remember who they are, and he refuses to turn the ring over to them when they ask for it, trying to stop his wish. He acts like the dummy is an old acquaintance of his, and he just wants to go to the nearest railway station with his dummy acquaintance.

Jerry sends the girls home to make some excuses for his and Jimmy’s absence, and he follows the now-elderly and wealthy Jimmy on the train to London. There, he learns that Jimmy and the living dummy have somehow acquired business offices, staff, and backstories. Other people seem to have somehow known the two of them for years (a warping of reality that makes Jerry’s head swim because neither of them existed in their current state before) and say that they are business rivals. Jerry pumps a boy who works at one of the offices for information, claiming that he’s a detective and is trying to reunite the elderly Jimmy with grieving relatives. The boy’s advice is that it will be difficult to get through to elderly Jimmy but that he might use the living dummy’s rivalry with elderly Jimmy to arrange things. The living dummy (now known as U. W. Ugli) helps Jerry to get control of the ring, and he wishes himself and Jimmy back to the house where Mabel lives.

The Ring’s True Power

Jimmy is restored to his younger self, and the children debate about what to do with the ring. They can see that it has some dangers. Mabel says that she ought to put it back in the treasure room, where she found it. However, while they’re in the treasure room, they begin to wonder if any of the other pieces of jewelry are magical, since the ring became an invisibility ring after Mabel pretended it was. Mabel can’t remember exactly what she said any of the other pieces of jewelry did because, at the time, she was just playing pretend and making things up. Then, something occurs to Mabel. She realizes that the ring only became an invisibility ring because she said it was one, and it turned into a wishing ring when they started calling it that. She says that proves that the ring does whatever they tell it to do, changing its powers to match whatever they say. To prove the point, she declares that the ring will now make people tall, and when she puts it on her finger, she is suddenly unnaturally tall.

Mabel’s experiment did prove the point, but they now have to hide Mabel until the effects wear off. The children get a picnic from Mabel’s aunt and go to hide out in the woods overnight. However, Mabel complicates things when she turns the ring into a wishing ring, and then, she accidentally turns herself into a statue. The children have a nighttime adventure with some living statues, learning that all statues apparently have the ability to come to life at night. They can also swim, so they have a nice swim and a feast. The statue of Hermes tells the children that “‘The ring is the heart of the magic … Ask at the moonrise on the fourteenth day, and you shall know all.'”

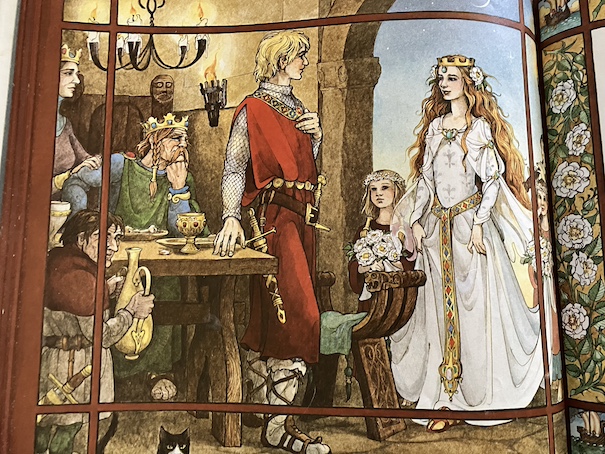

Then, the children learn that Lord Yalding, the man who owns the big house, is planning to come, and that he is thinking of renting the house to a wealthy American. Mabel’s aunt is busy, getting the house ready for Lord Yalding and the American. However, it turns out that the children have already met Lord Yalding without realizing it, and with the ring and the treasures in the hidden treasure room, they have the power to secure his future and reunite him with his lost love … if only they can figure out how to manage the ring’s power without causing any more chaos.

The book is now public domain and available to borrow and read for free online through Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive (multiple copies), including an audio recording from Librivox. The story was made into a BBC television miniseries in 1979, but it’s difficult to find a copy these days. As of this writing (April 2024), the only dvd release was in Australia in 2013. Sometimes, clips of it appear on YouTube.

My Reaction and Some Spoilers

For the first part of the book, it isn’t obvious that there will be any real magic in the story. At first, the children are all just playing pretend with each other, and even when Mabel turns invisible, it’s possible to believe that the children might still be playing pretend and letting their imaginations run away with them. Because the adults don’t seem that concerned about Mabel, I thought that they might have been humoring the children in their game, but the children later realize that the ring has the effect of muting people’s concerns for the one wearing it, even if they’re doing something bizarre or dangerous. That ends when the person takes off the ring, and people become more concerned about them and where they’ve been. The magic in the story is real, and as the story continues it involves too many other people, even adults and various bystanders, for it to just be a game.

Throughout the book, various adults experience the effects of the magic ring and witness things that the children do with it. They come up with various explanations for what they’ve witnessed, so they can disregard it, but they unquestionably experience magical events along with the children and have some consequences from the children’s adventures. While Jerry retrieves Jimmy from London when he accidentally turns himself old and wealthy, they never do retrieve the living dummy, so U. W. Ugli remains doing business there until his magic finally wears off. His employees don’t seem to know what he is and have memories of having worked for him for years, so they report him missing when he finally disappears, and the notice appears in the newspaper.

There’s a lot of humor in the story as the children experiment with the magic, deal with the consequences of their adventures, and try to invent excuses to explain away the inexplicable. There are times when they do try to tell adults the truth about what they’ve been doing and what’s happening, but most of the time, the adults don’t believe them. Sometimes, they feel a little bad about lying to adults and making up stories, but they have to resort to that because nobody really believes the incredible truth.

When the children start telling Lord Yalding the stories of their magical adventures and about the treasures they’ve found in the house, they are unable to prove what they say at first. Lord Yalding gets a chance to experience the magic himself, he thinks that he’s going crazy. At the proper time, the ring’s magic reveals itself to Lord Yalding, his love, and the children so they can all see the true magic and learn the ring’s history, which is a story of magic and tragic love. Lord Yalding comes to understand that he is not crazy and that the magic is real. His lover makes one final wish that turns the wishing ring into a wedding ring. The magic ends, and the castle and grounds are changed because of it, becoming less grand and more ordinary, but Lord Yalding and his bride are able to have their happy-ever-after.

I thought it was interesting that the author provided a backstory for the magic ring, explaining where it came from and its effect on the house and its grounds. I didn’t think there were many clues to that backstory provided along the way, and some buildup to the explanation would have been nice. However, I recognize that the author didn’t have to provide any explanation for the magic at all. Many other fantasy stories don’t offer explanations for magical objects, leaving that up to readers’ imaginations, because the focus is more on the effects of the magic rather than its origins.

As far as we know, the children’s other sister, the one who was sick with measles in the beginning, never finds out what her siblings have been doing during this particular school break. The children remain close to Lord Yalding and his wife, and they host them at their house during school breaks afterward. In fact, it sounds like they spend more time with Lord and Lady Yalding than they do with their parents.

Overall, I enjoyed the story. E. Nesbit’s fantasy stories are children’s classics, and they have influenced other children’s fantasy books that came after them, especially Edward Eager’s Tales of Magic series.

Problem Points

Although the original story is now public domain, there are different versions of this book because there are simplified forms of the story for younger children, and some newer editions have removed some of the problematic parts of the story. Some of E. Nesbit’s books contain problematic racial language or stereotypes or have children doing things that would be unacceptable by modern standards. In this book, such incidents are relatively mild, and their absence wouldn’t materially change the character of the story.

For example, when Jerry dresses up an conjurer from India, he uses black face as part of his costume. In the 21st century, use of black face is considered derogatory toward people with dark skin. In a way, Jerry’s costume is played for comedy because it’s made from pieces of his school uniform, and someone points out that he’s left out spots in his skin makeup. Nobody believes that he’s a real conjurer from India, although they are impressed by his act because they can’t figure out how he accomplishes his tricks.

There is also some anti-Catholic sentiment, although the children seem to say certain things because they’ve gleaned them from sensational novels or things other people have said, and the author does correct for it. The first instance of this comes from Mabel’s concept of the dark deeds done in convents, which she has apparently learned by reading gothic novels. I’ve read some old gothic novels myself, and the idea that sinister things happen in secrecy in convents and abbeys was a popular concept from 18th and 19th century literature. It’s partly due to anti-Catholic sentiment and, probably, because the idea of a closed society that isn’t open to the general public makes for a compelling setting for dark secrets, somewhat like the way secret societies and boarding schools have become the setting for sinister happenings and dark deeds in Dark Academia literature. However, the other does have the character of the French teacher contradict this view of convents with a more benevolent and realistic one, that the people in them are caring but strict. There is one other comment that Jimmy makes in the story when he’s arguing with Mabel, when he seems to be implying something about Jesuits, a branch of Catholic priesthood:

“If you’d been a man,” said Jimmy witheringly, “you’d have been a beastly Jesuit, and hid up chimneys.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what this comment meant, although I think it might be a reference to the ways Catholics hid priests in priest holes, little hidden rooms, when they were at risk for arrest, torture, and even execution in Elizabethan England. Some of these little hiding places were in fireplaces, which I think is what the reference to hiding in chimneys means. At the time, the children were arguing about bravery, so I think Jimmy is implying that Mabel is the type to run and hide in the face of danger. (That might actually be the best option when there’s real danger. Just saying.) If I’ve understood his meaning, that makes Jimmy’s comment more of a slur against Mabel’s bravery than against Jesuits, although he does still call the Jesuits “beastly”, and he’s implying that’s a bad thing to be.

When you read public domain versions of the story online, they will have these elements in the story because they were part of the original book. However, if you find a physical copy in a library, it may or may not have these elements, depending on the printing. If it was printed during the late 20th century or any time during the 21st century, there is a good chance (although not completely guaranteed) that it’s a revised version and may have these parts written out or at least toned down.