Mystery of the Strange Traveler by Phyllis A. Whitney, 1951.

This book was originally published under the title The Island of Dark Woods.

Laurie Kane and her older sister, Celia, are traveling by train without their parents to visit their Aunt Serena in New York. Aunt Serena has invited the girls to come stay with her while their parents are traveling in Asia for one of their father’s newspaper assignments. In her letter to the family, Aunt Serena hints at exciting things that are happening. She used to be a schoolteacher, but she says that she’s starting a new business, and the girls can help her with it, although she won’t say what it is until they arrive. Also, Aunt Serena has recently moved to a new house. When their father sees where she’s living now, he’s intrigued because it’s the location of their “ancestral mystery.” He would tell the girls the story himself, but Aunt Serena says in her letter that she would like to be the one to tell them about it. There father says that Aunt Serena loves being tantalizing and mysterious. Laurie, who loves mystery stories, wonders about it all the way to New York.

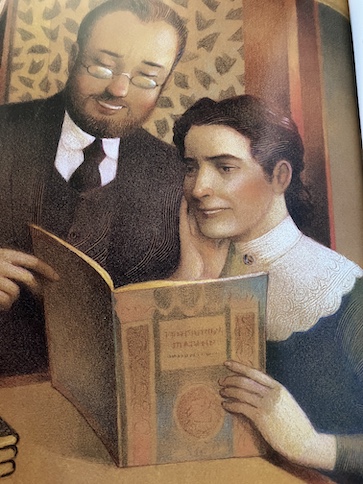

Aunt Serena lives in a wooded area on Staten Island, near Clove Lakes Park. She has a small red brick house with another outbuilding on her property that she says used to be an old cobbler’s shop. Her new business idea is to turn it into a small bookshop. Laurie loves it immediately because she loves books. She wants to be an author herself, and Aunt Serena says that she might even get a chance to meet her favorite author, Katherine Parsons, because she lives in the area. Celia is the practical one, and she asks Aunt Serena all the practical questions about how she plans to get people to come to her little shop when there are no other stores around them to draw customers in. Aunt Serena says that she’s not expecting her shop to turn into a big business. It’s more of a small hobby business to bring in a little extra money and also be a fun activity.

Laurie and Celia begin unpacking some of the books that Aunt Serena will sell in her small shop, and Laurie is pleased to see a collection of books by Katherine Parsons. On the back of one of the books, there’s a picture of the author and a short biography. Laurie is pleased to note that Katherine Parsons is left-handed, like herself. There are times when Laurie has difficult with things because she’s left-handed, and she feels a kinship toward the author because she shares that trait.

Meanwhile, Celia has noticed that there is a boy next door, moving the lawn. Laurie is more interested in books than boys, so she doesn’t find this exciting news. Celia tries to get the boy’s attention, but he seems to be ignoring her. When he does seem to notice the girls, he turns away quickly, like he wants to avoid them. Celia points out to Laurie how the house where the boy is looks very different from the rest of the houses around it – big, old-fashioned, dark, and creepy. Laurie comments that it looks haunted, and their Aunt Serena surprises them by saying it is.

The boy, Norman, lives with his grandfather, Mr. Bennett, in the old house. Mr. Bennett is a difficult man, and Aunt Serena admits that she got on his bad side when she first moved to the area by asking him if she could buy his house. Aunt Serena admits that she didn’t actually want to buy Mr. Bennett’s house; she was only using her inquiry as an excuse to talk to him and maybe get a look inside the house. However, Mr. Bennett took offense at the inquiry.

There is another boy in the neighborhood called Russ Sperry, and he’s friendlier. His mother sends him to bring a cake to Aunt Serena, and Aunt Serena says that she hopes he will be friends with the girls and show them around. Russ stays awhile to have some cake and chat, and he mentions that Norman Bennett’s father is in South America because he has a job there, which is why he’s staying with his grandfather. Aunt Serena says that Norman’s mother is dead and that his father rarely comes home. She doesn’t approve of the lonely way Norman’s grandfather seems to be raising him because it seems like Norman doesn’t have any friends. Laurie thinks that Norman’s loneliness is at least partly his own fault because he seems to avoid contact with people when she and Celia try to approach him. Celia decides that Russ is cute, but Laurie finds herself intrigued by Norman, not because she wants to flirt with him but because there’s an element of mystery about him.

The girls try to ask Aunt Serena more about what she means when she says that the Bennett house is haunted, but she says that she would rather talk about that later. She gets the girls busy unpacking their belongings, arranging things in her shop, and talking to Russ about the area. Russ helps to explain the geography of Staten Island, and Aunt Serena tells the girls more about the history of the area. Aunt Serena mentions that there are dances in the park on Wednesday nights, which sounds exciting to Celia. When Laurie spots Norman passing by, wearing riding clothes, Russ explains that there are a couple of stables in the area, where people can rent horses. There are plenty of things for the girls to do in the area, and Aunt Serena begins planning an opening party for her bookshop, with Katherine Parsons there as a special guest to sign her books.

Laurie is excited about the party and the opportunity to meet Katherine Parsons, but she continues to think about the mystery of why Norman seems so unfriendly. Soon, other strange things start happening. One night, she sees a light in Aunt Serena’s bookshop, as if someone were sneaking around in there. However, when Laurie goes to wake Aunt Serena to show her, the light is gone, and the next day, there aren’t any obvious signs that anything in the shop was disturbed.

When Laurie has a chance encounter with Mr. Bennett, where she asks him if he’s ever seen the ghost that haunts his house, he says, no he hasn’t seen it. The ghost is supposedly a phantom stagecoach, but Mr. Bennett doesn’t believe it exists. Once Laurie knows that there’s supposed to be a phantom stagecoach, she tries to press Aunt Serena for more details, but Aunt Serena refuses to tell them the rest of the story until she can tell them on a gray, stormy day, when the atmosphere is right.

When a stormy day comes and Aunt Serena agrees to tell the story, she allows Celia and Laurie to invite Russ and Norman over to hear it, too. Norman comes to hear the story without his grandfather’s permission because he’s always known there was some story about the house, but his grandfather hasn’t wanted to talk to him about it. When Aunt Serena tells the ghost story, the connections between the Kane family and the Bennett family become clear.

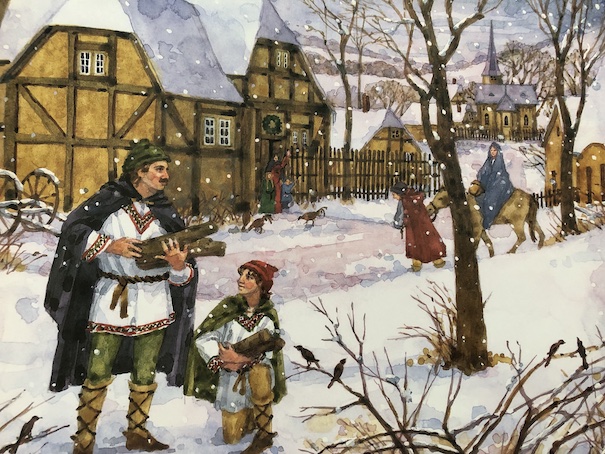

About 100 years before, there was a stagecoach route that ran through this area. One stormy day, a stagecoach was passing through the area, and one of the passengers, a woman with an infant daughter, was seriously ill and had become delirious. The stagecoach driver sought help at the Bennett house. The Bennetts brought the sick woman inside the house, along with the infant daughter. The stagecoach driver sent a doctor to tend to the woman, but she died in the Bennett house. They had no idea who the woman was and were unable to trace her origins or family. If the woman had a husband or the infant girl had a living father, the man never showed up to inquire after his wife or to claim the baby. All the Bennetts had do go on were the meager possessions the woman was carrying with her, and the little girl herself, whose last name was unknown but the mother had called “Serena.”

At this point, Serena explains that this Serena was the ancestor of the Kane family, the great-grandmother of Celia and Laurie. Since nobody was able to discover where she and her mother came from or locate any relative, the Bennetts adopted the first Serena and raised her until she grew up, got married, and moved away from the island. However, local people still tell stories about the terrible day when the first Serena and her ill mother were brought to the area, claiming to have seen a ghostly stagecoach pull up to the Bennett house and a ghostly woman get out.

Laurie is intrigued by the mystery surrounding her family’s origins. Aunt Serena shows them some of the belongings that the first Serena’s mother had when she died, which have been passed down as heirlooms. There was a doll with doll clothes, a woman’s dress with bonnet and gloves, a sewing kit, a fan, an old novel the woman must have been reading at the time, and a purse containing a very old coin. The old coin is another oddity about this strange situation because it dates from before the Revolutionary War and would have been long obsolete by the time the woman died during the 19th century. Is it still possible to solve a mystery that’s about 100 years old? Will Laurie and her family ever learn who their ancestors really were? Why does Mr. Bennett not want them to visit his house or talk about the old mystery or the ghost story? Does he know more about them than he wants to admit?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction and Themes

The mystery in the story unfolds slowly, which might make people who are used to faster-paced modern stories a little impatient. Aunt Serena takes quite a while from the time when she first mentions that the house next door is haunted until she actually explains what the ghost is supposed to be and what the mystery surrounding their family is. However, Aunt Serena values atmosphere, so the story could appeal to people who don’t mind a slower-paced mystery as long as it has a good atmosphere.

When the mystery does begin, some parts are resolved quickly and others are more of a puzzle. The idea of an orphan with an unknown identity and a hidden past is always intriguing. The light in the bookshop at night, on the other hand, turns out to be less of a mystery, and Mr. Bennett’s reluctance to discuss the ghost story and the old mystery turns out to be nothing sinister. Mr. Bennett doesn’t really have any hidden knowledge about the orphaned child or her dead mother. It’s just that he’s a very reclusive person who craves peace and quiet so he can work on his private projects. He also has some resentment toward the Kane family because, while they used to be very close, Laurie’s grandfather was the one who inspired Mr. Bennett’s son to take a job in another country, which is why Mr. Bennett and Norman rarely see him. By the end of the story, though, things get patched up between them.

Every time the matter of the mysterious orphan and the question of whether or not the house is haunted by her mother is raised, Mr. Bennett has had to deal with a bunch of people and reporters stopping by his house, harassing him with questions and asking for tours of the place, and he’s sick of it. He doesn’t want Aunt Serena or the kids raising the issue again because he doesn’t want to deal with everybody’s questions anymore, and he has no more information to give anyone. As far as he’s concerned, the mystery is unsolvable because he thinks whatever trail there might have been has long since grown cold, and if it were ever possible to learn the dead woman’s identity or the real origins of the child, someone else would have figured it out a long time ago. However, Laurie tells Mr. Bennett that she thinks that there’s still a chance to figure it out, and that plays into one of the major themes of the story.

The Atmosphere and Location

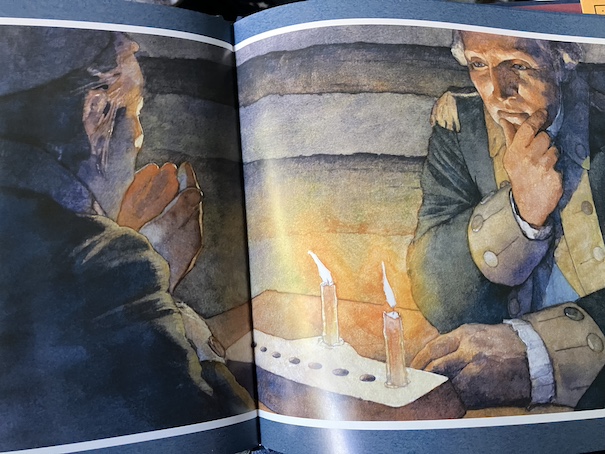

The atmosphere of the story is pleasant, with Aunt Serena’s cheery little house decorated with bowls of wildflowers and her little bookshop. Aunt Serena greatly believes in establishing atmosphere, creating scene, and setting a mood. On the stormy day when Aunt Serena finally tells the girls the local ghost story, she makes it a point to set the atmosphere for the story by making popcorn and lighting candles.

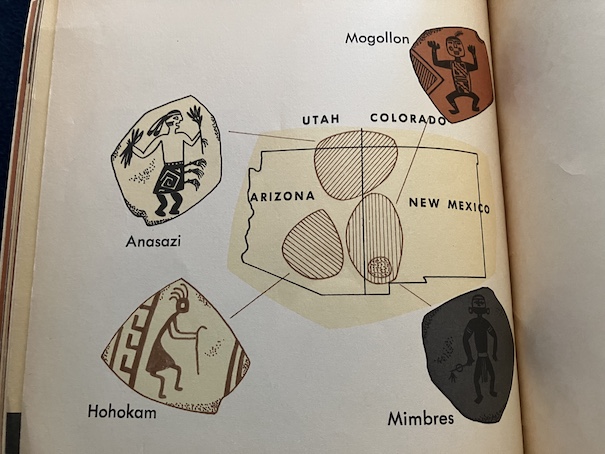

Like other books by Phyllis Whitney, this story is set in a real location and uses some of the history of that location. The original title of this book came from the original Native American name for Staten Island, Monocknong, which the fictional author in the story, Katherine Parsons says means “The Island of Dark Woods.” Mr. Bennett disagrees, though, saying that it actually might mean, “The Place of the Bad Woods,” and they debate about different possible translations and meanings of the phrase. The history of the Staten Island plays directly into the story because it turns out that Laurie’s ancestors were involved with the historical events of the area, particularly Santa Ana’s stay on Staten Island after the Battle of the Alamo in Texas that was part of the Texas Revolution against Mexico.

A couple of other points I’d like to make regarding history are about race in the story. Toward the end of the book, Mr. Bennett hires “a young colored woman” as a housekeeper. “Colored” is a dated term in the 21st century, but this book was written in the 1950s, when that was considered one of the more polite ways to refer to black people. The popular terms we use now (“black” as the informal generic term and “African American” as the formal term specific to black people of African descent who live in the United States) came into use after the Civil Rights Movement as people tried to distance themselves from older terms as a way to shed the emotional baggage associated with them. The housekeeper, Anna, becomes friendly with Laurie, and she offers her a new perspective and some helpful advice about a different approach to tracing her family’s roots. Anna enters the story late, so she doesn’t appear much, but she is helpful, and I didn’t notice anything particularly stereotypical about her, although I suppose the idea of a black person in domestic service might be kind of cliche.

The other thing I wanted to mention is that American Indians are referred to multiple times in the story when the characters discuss the island’s history. The characters always refer to them as just “Indians” instead of “American Indians” or “Native Americans”, which is typical of the 1950s. At one point, Celia and Laurie are discussing their role in the island’s history. Celia talks about how she was glad that she wasn’t around then because there were massacres and “the Dutch kept buying the island from the Indians and the Indians kept taking it back.” However, Laurie says that was “because the white men cheated them.” I appreciated that Laurie acknowledged that, and I think that this exchange not only highlights some of the stereotypical views people had in the 1950s about Native Americans and history, but also differences between the ways Celia and Laurie look at other people. I have more to say about that below, but Celia tends to cling toward accepted views and the general social rules of society while Laurie has a talent for empathy and looking at situations from another person’s perspective. I’ve noticed that the author, Phyllis Whitney, has used this technique in other books of hers to subtly challenge stereotypes, pointing out that different groups of people have their own perspective and their own side of the story.

This book is fun for book lovers. Laurie’s favorite author, Katherine Parsons, is fictional, but the story captures the spirit of book lovers. It turns out that Norman is a book lover, too, and Laurie is able to draw him out and bond with him over their shared love of books. Aunt Serena also praises Laurie for her ability feel empathy for other people, a quality that she believes comes partly from Laurie being a book lover. After all, readers are accustomed to the idea of seeing circumstances through the eyes of someone else and experiencing their thought processes when they read a story. Aunt Serena believes that one of the benefits of reading it that it helps to cultivate a person’s skills in using empathy to understand other people and that readers carry that technique over into the real world.

I will say, though, that Laurie’s story took an unexpected turn. Laurie is a book lover, but through her association with Katherine Parsons, she unexpectedly realizes that, while she’s always dreamed of writing stories and being published, she doesn’t actually like the writing process. She enjoys the stories other people have written, and she has a knack for understanding characters, whether real or on the page, but she’s surprised to realize that the routine of writing doesn’t appeal to her. She feels a little sad at the realization because it means giving up an old dream but also a little relief because her life is now open to more possibilities that she might like better.

The Sisters and 1950s Social Rules

I also enjoyed the relationship between the two sisters in the story. They get on each other’s nerves and fight with each other sometimes, but they also care about each other and make up with each other after fighting. Celia, as the older sister, is more interested in boys than Laurie is, and she has all kinds of social rules about how to talk to boys and how to get their attention. Laurie knows that Celia and her friends talk about these things a lot, but Laurie doesn’t really understand all of their little rules and thinks a lot of them sound silly, like the idea that girls can’t invite boys to things but have to wait for the boys to ask them or that they should pretend like they’re not too interested in a boy so the boy will approach them first. This book was written in the 1950s, so a lot of Celia’s social expectations about how girls and boys should act around each other sound dated, but I enjoyed Laurie questioning Celia’s rules.

Laurie thinks it more important to know about what specific people like and how to appeal to them as individuals than to adhere to more general social rules. This is especially apparent when the girls try to get Mr. Bennett to let them in his house and talk to him. When the sisters compete to ingratiate themselves to Mr. Bennett so they can get access to the house and talk to him about the mystery, their different approaches play on their concepts of social rules and human empathy. Celia tries a very conventional approach, trying to appeal to Mr. Bennett in a general way, but Laurie decides that “Mr. Bennett was too much of an individual to be governed by rules that worked for most people” and tailors her approach to him as an eccentric individual.

Celia’s idea is to make some homemade cupcakes and take them to Mr. Bennett as a gift because she believes in the old axiom that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. As Laurie suspects, though, this approach falls flat because Mr. Bennett isn’t interested in baked goods. Laurie has a better idea of what Mr. Bennett really likes because she has talked to Norman about him, and she decides that the way to get his attention is to demonstrate a shared interest in something he likes. Knowing that he likes nature more than anything else, she starts putting together a collection of interesting leaves and asks Mr. Bennett if he can help identify them. Mr. Bennett isn’t really impressed by her collection because she didn’t mount the collection properly, most of her collection is very common leaves that he thinks she should be able to identify if she knew anything about trees, and she also included a sample of poison ivy, which she should have known better than to touch. However, he is sufficiently amused by her efforts and her mistake to talk to her for a few minutes.

No Man is an Island

One of the major themes of the story is that “No man is an island”, meaning that people do need other people. Aunt Serena is concerned that Mr. Bennett’s obsession with solitude is hurting his grandson because he’s making it difficult for Norman to make friends. Mr. Bennett has forbidden Norman to bring any other kids to the house because he doesn’t want to deal with the noise and disturbance. Because she’s been a teacher, Aunt Serena knows that Norman needs more opportunities to socialize with his peers. Mr. Bennett doesn’t even seem to pay much attention to Norman himself because he’s too absorbed in his own work.

What Laurie points out to Mr. Bennett when Mr. Bennett tries to tell the kids that the old mystery is unsolvable is that a group of people working together can accomplish more than any one person, working alone. They don’t have many clues to the past, but just because they don’t all make sense to any one of them doesn’t mean that parts of them wouldn’t make sense to different people. By pooling their knowledge and consulting other people, they could still put together the pieces of the past.

Along the way, Laurie also makes Mr. Bennett realize that there are many things he doesn’t know about Norman. Even though he and Norman have been living alone together for a long time, Mr. Bennett hasn’t paid much attention to Norman or things Norman has been doing. Norman has felt lonely and neglected, although he hasn’t wanted to admit how much. When Mr. Bennett realizes that Norman is an artist and has been developing his skills to an impressive degree without him even seeing any of Norman’s projects, he realizes that he has been too absorbed in his own concerns and starts to make an effort to learn more about what’s happening in the lives of the people around him. This is a similar situation to a grandmother in another of the author’s books, Mystery of the Angry Idol.