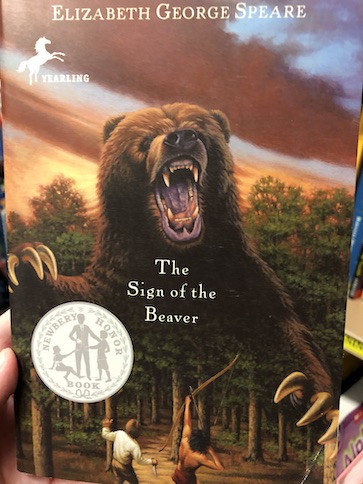

Sign of the Beaver by Elizabeth George Speare, 1983.

The story begins in the late 1760s with twelve-year-old Matt’s father leaving him alone in the log cabin that he and his father built for their family in the Maine territory. The rest of their family is still in Massachusetts, and Matt’s father is going to get them and bring them to their new home. Their family will be the very first to settle in what will soon be a new township. However, for now, Matt is alone at their cabin, surrounded by miles of wilderness, while he waits for his father to return and the rest of his family to arrive. Matt will be looking after the cabin and the field of corn that he and his father planted, but he finds the silence and solitude unnerving.

Before he left, Matt’s father left his watch and rifle with Matt. After his father leaves, Matt tries the rifle. He doesn’t hit anything, and he decides that it will take getting used to. He learns to hunt with it, and Matt finds that he is very busy with hunting, fishing, and chores, which helps pass the time. Every day, he makes a notch on a stick to mark the days that pass.

Gradually, Matt becomes aware that someone is watching him. Someone seems to be hiding and following him. Since there are no other white families living for miles around, he can only assume that it must be an “Indian” (Native American). They know that there have been some in the area, although they haven’t really met any yet. Matt finds the prospect a little worrying because he isn’t sure what to expect from them, but his father always told him that, if he met an Indian, he should just be polite and respectful. Matt is nervous that whoever is watching him is also hiding from him, though.

One day, Matt hears someone wearing heavy boots tramping in the woods, and Matt thinks that maybe his father has returned early for some reason. However, it turns out to be a stranger in a blue army uniform. Although Matt has missed having company, he finds himself reluctant to talk much to this stranger, and he doesn’t want the man to know that he is there completely alone. Still, the stranger is hungry, so Matt agrees to let him share a meal with him. The stranger, who calls himself Ben, stays the night with Matt, uninvited. Matt can’t bring himself to turn away someone who needs hospitality in the wilderness, and Ben tells him stories of his past adventures. Matt still has misgivings about Ben, and he’s sure his stories are tall tales. When Ben mentions leaving a town because there was trouble there, Matt thinks maybe Ben ran away because he’s a criminal. Matt plans to stay awake that night to keep an eye on Ben, but he eventually falls asleep. When he wakes up, Ben is gone, and so is his father’s rifle. Ben is a thief! Matt realizes that he was right to be suspicious of Ben and is angry that he let him get away with stealing the rifle.

Without that rifle, Matt can’t hunt. He can still feed himself through fishing, but he loses more of his supplies when he forgets to properly bar the door while he’s out fishing, and a bear eats most of the food in the cabin. Reduced to eating only fish, Matt gives in to temptation and tries to get some honey from some bees he finds in a nearby tree. It’s a bad idea, but this decision changes everything for Matt.

Matt is badly stung by the bees, and when he tries to escape them in the water, he nearly drowns. Fortunately, Matt is saved from drowning by the Indians who have been watching him. It turns out to be a grandfather and his grandson. The grandfather, Saknis, takes Matt back to his cabin, brings him food, and treats his wounds. When he realizes that Matt hurt his ankle and lost his boot in the water, he gives Matt a crutch to use for walking and a new pair of moccasins to wear.

Matt is both grateful for this much-needed help but also very self-conscious about it. He can tell that the grandson, Attean, doesn’t like him and thinks that he’s a fool for getting hurt like this, which is embarrassing. Matt also thinks that he should repay them for what they’ve given him, but he doesn’t have much to offer. The only thing he can think of to give them is the only book he owns, a copy of Robinson Crusoe. Matt is embarrassed when he realizes that the Saknis can’t read, and he thinks maybe he will be offended at this type of gift, but the older man realizes that Matt’s knowledge of reading is a gift that they badly need.

In broken English, the old man explains that his people have made treaties with white people before, but because they can’t read English, they never really know what’s written in the treaties. When white people break the treaties or tell them that they’re no longer allowed in certain areas of land, there isn’t much they can do, since they don’t even know for certain what was in the original agreements. He realizes that his people can’t afford to be ignorant. There are more white people moving into their territory all the time, and his people will have to know how to deal with them. Therefore, Saknis proposes a kind of treaty with Matt: they will continue to bring Matt food if Matt teaches Attean to read.

Attean immediately protests this plan. He really doesn’t like Matt, or any white people in general, and he doesn’t want these reading lessons. However, his grandfather is firm that this is something he needs to do. Matt also isn’t sure about this plan. He does owe them for their help, but he’s never taught anybody to read before. His own early lessons didn’t go particularly well, although he likes reading Robinson Crusoe now. Also, Matt thinks of Attean as being a “savage” and a “heathen” who doesn’t even really want to learn, so he’s not confident that the reading lessons are going to go well. Still, Matt does owe them for saving him and could use their continued help while he recovers from his injuries, so all he can do is try.

When Attean gets frustrated during the first reading lesson and storms out of Matt’s cabin, Matt thinks that the lessons are already over. Yet, Attean does return for more lessons. Gradually, Matt thinks of ways to make the lessons more interesting to Attean, reading the most exciting parts of Robinson Crusoe out loud to Attean to get him interested in reading the story himself and finding out what will happen to the main character. It isn’t easy to get Attean interested in learning because Attean is initially determined not to be interested or impressed by anything Matt has to say.

When Matt becomes curious about some of the things Attean and his tribe do, like how Attean hunts rabbits without a gun, Attean opens up a little and shows Matt some of the things he knows. Matt begins to admire some of the unique skills Attean shows him and learns to use them for himself. Matt is aware that his first efforts must look clumsy and childish to Attean as he tries to learn skills that Attean has known for years, but it puts the boys on a more equal footing with each other. Each of them has something to learn from the other, and it’s all right for each of them to look a little awkward to the other while learning. Matt gets embarrassed sometimes when he does something clumsy in front of Attean, but he learns that he must also persevere. Attean teaches him some good, practical skills for making things without using some of the manufactured goods that he and his father brought with them from Massachusetts. When Matt loses his only fish hook, Attean shows him how to make a new one. Attean teaches Matt to be self-reliant and to use new methods to accomplish his goals.

During the part where Matt reads the part of Robinson Crusoe where Robinson Crusoe rescues the man he calls Friday, and Friday, out of gratitude, becomes his slave, Attean protests that would never happen in real life. Attean says that he would rather die than become a slave. Matt is surprised because he never really thought that much about how someone like Friday would feel in real life. Matt learns to look at the story as Attean would, reading the best pieces to him, the ones that emphasize the friendship between the two characters rather than servitude.

Gradually, Matt and Attean become friends. Matt doesn’t think he’s very good at teaching Attean to read, but Attean does slowly learn. Although Attean resists learning to read because he’s trying to prove that he doesn’t need this skill that he associates only with white people, his spoken English becomes better as he and Matt talk. Attean admits that he tells parts of Robinson Crusoe to his people, and they enjoy hearing them, so Matt moves on to stories from his father’s Bible. Attean finds the Bible stories interesting and compares them to stories that his people already tell. (It is interesting, for example, how many civilizations around the world tell stories about great floods.) The boys are fascinated by the common themes in their stories.

The boys also enjoy doing things together, and Matt feels less lonely when Attean comes to visit. Matt doesn’t always like Attean because he has a disdainful attitude toward him, but they learn to trust each other, and they find interesting things to do together. Matt comes to realize that his irritation at Attean’s attitude is because it’s so difficult to earn Attean’s respect, and he really wants Attean’s respect. Although Matt doesn’t like Attean’s attitude toward white people, he does agree with Attean about some things, and he has to admit that he cares about what Attean thinks. Matt does get some respect from Attean later when the boys have a hair-raising encounter with a bear. Attean is the one who actually kills it, but Matt proves his usefulness during the struggle. Matt also comes to understand Attean’s resentment against white people when Attean eventually tells him that he’s an orphan and that his parents were killed by white people. That’s why he lives with his grandparents.

As time goes by, Matt becomes increasingly worried about whether or not his family will ever arrive. He worries that maybe something happened to his father and that the rest of the family won’t know where the cabin is and won’t be able to find him. When it passes the time when his family should have arrived, Matt fears that maybe they will never come at all. What if he is left alone? He has survived so far, with some help from Attean and his people, but can he live alone forever? Or could there be a place for him among Attean’s people?

Saknis has also been thinking about this, and he has noticed that Matt’s family has not yet come. He knows that it would be dangerous for the boy to remain alone in the cabin when winter comes. As the seasons change, the Native Americans are preparing to move to their winter hunting grounds. Saknis invites Matt to come with them, and Matt has to decide whether to accept the offer or stay and wait for his family.

This book is a Newbery Honor Book. It’s available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction and Spoilers

This story reminds me a little of The Courage of Sarah Noble, where an 18th century white child who is afraid of Native Americans comes to learn more about them by living with them and interacting with them. I actually read The Sign of the Beaver when I was a child, and I only read The Courage of Sarah Noble as an adult. I’m not sure now if I prefer one of these books over the other. For a long time, I forgot the title of The Sign of the Beaver, although I did like this book the first time I read it. I remembered the concept of the boy living alone while he waited for the rest of the family to join him. One part that stuck in my mind the most was the part near the end of the story where Matt makes a cradle because he knows that his mother was expecting a baby when he last saw her and thinks that it would be nice to have a cradle ready for his new younger sibling, but when his family arrives, he is told that the baby died. That tragic image just stayed with me for years.

Some of the prejudiced language in the story, like “savage” and “heathen” and some anti-Catholic talk from Ben early on, is a little uncomfortable, but this is one of those stories about changing attitudes and overcoming prejudice. The main character has to show some fearful and/or prejudiced thoughts toward Native American initially for readers to appreciate how far he comes and how much his thinking changes after he makes friends with them and learns more about them.

Ben, of course, is a villain character, so his prejudiced talk is a reflection of that. He’s selfish and a thief, so his views of other people are based on what puts him in the best light or justifies things that he’s done. When he talks about the people of the last town he was in being against him and making trouble so he had to leave, both the readers and Matt realize that Ben was the one who started the trouble. Ben blames other people for problems he creates himself. The stories he tells Matt about his earlier, supposedly brave adventures are based around the French and Indian War, which is where the Catholics enter the discussion.

Several times during the story, Attean uses the word “squaw” to refer to women. I didn’t think too much about that sort of thing when I was a child because I assumed that both the author and characters in books that used that term knew what it meant and were using it correctly. Since then, I’ve heard that it actually has a rather vulgar meaning, although I’ve also heard conflicting information that it’s not always vulgar. The contradictory accounts make it a little confusing, but according to the best explanations I’ve read, the contradictions about the meaning of this word have to do with similar-sounding words in different Native American languages. Not all Native American tribes have the same traditional language, and some have words that sound like “squaw” and refer to females in a general way, while others have words with a similar sound that refer to female anatomy in a more vulgar way. For that reason, something that might seem innocuous to one native speaker might sound crude to another, and non-native speakers of any of the languages involved may not fully understand all the connotations of the word. In the end, I’m not sure how much of this the author of this book understood, but my conclusion is that it’s best not to use certain words unless you’re sure of their meaning, not only to you but to your audience. I only use the word here to make it clear which word appears in the book. Other than that, I don’t think this word is a necessary one, at least not for me. I understand what Attean is referring to in the context of the story, and I think that’s what really matters in this particular case. Whether that’s the right word for Attean’s tribe to use at this point in history would be more a matter for a linguist. I’m willing to accept it in the book as long as readers understand the context of the situation and are content to leave the word in the book and not use it themselves outside the context of the story.

When Attean talks about women in the story, it’s typically to point out certain types of work that he considers women’s work instead of men’s work. Matt is a little offended sometimes when Attean tells him that some chore he’s doing is for women instead of men. Matt’s family doesn’t have the same standards for dividing up chores as Attean’s tribe does, and the fact is that Matt is living alone at the moment. There are no women in Matt’s cabin, only Matt. Any chore that needs to be done right now is Matt’s to do because there simply is no one else to do any of it for him. I think when Attean tells him that he’s doing women’s work, he’s trying to needle Matt because, otherwise, he comes off as sounding a little dense. Sure, Attean. We’ll just have the women who aren’t here do this stuff that needs doing right now. During the course of the story, Matt comes to appreciate how the Native Americans live differently because it makes sense for the place where they live and their circumstances, but this is one instance where Attean could be a little more understanding about Matt’s circumstances.

One thing that I had completely forgotten about in this story was the part where Matt thinks about how Attean smells bad. Earlier, when I did a post about Mystery of the Pirate’s Ghost by Elizabeth Honness, I was irritated at the author for having one of the characters imagining smelly Native Americans because I had never heard of that as a stereotype before (I thought at the time), and I didn’t know where that idea came from. A site reader suggested that the trope came from the Little House on the Prairie series because there is talk like that in those books, but The Sign of the Beaver actually offers an immediate explanation as soon as Matt thinks about the cause of the smell. Matt realizes that Attean has smeared a kind of smelly grease on his body that is meant to repel mosquitoes. Matt has heard of people doing this before, and he understands that there is a useful purpose behind it, but he just hates the smell so much that he thinks he’d rather just put up with the mosquitoes. That explanation really helps to put everything into context. When there’s no explanation about things like this in stories, it makes it sound like Native Americans are just smelly because they’re “savages” who don’t bathe or something, but when you hear the explanation, it’s just that the smell is an inconvenient side effect from something that has a real, practical purpose. It might be unappealing to Matt, but there is a point to it. So, on the one hand, I feel a little bad about getting down on Elizabeth Honness for throwing that idea into her story without an apparent basis, but still irritated because, if she knew that was the explanation, she could have said something about it instead of just throwing that out there, like everyone reading the story would already know. I have similar feelings about some of the things Laura Ingalls Wilder put in her books, too. Context is important, and some authors are better at providing it than others. I also think that context is something that books from the late 20th century and early 21st century often provide better than books from earlier decades, although there are some exceptions.

At the end of the story, we don’t know for sure whether Matt and Attean will meet again. When Matt’s family arrives, they tell him that other white families will be arriving soon. Matt knows that the tribe he befriended will likely lose their hunting grounds to the town that will be built there. Matt is concerned for their future, but he is glad to be reunited with his family and still considers Attean his friend.