The House in Hiding by Elinor Lyon, 1950.

This is the first book in the Ian and Sovra series, which takes place in Scotland.

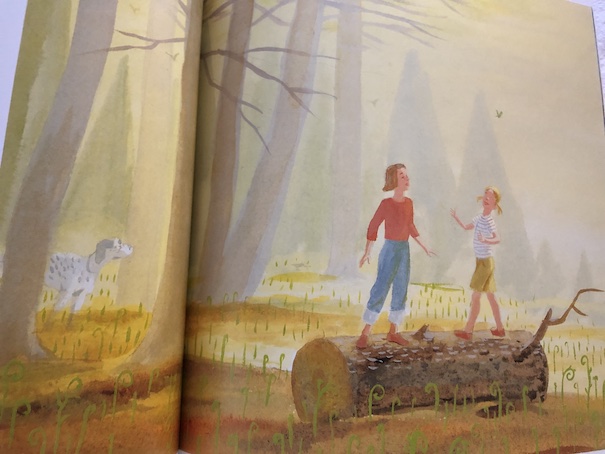

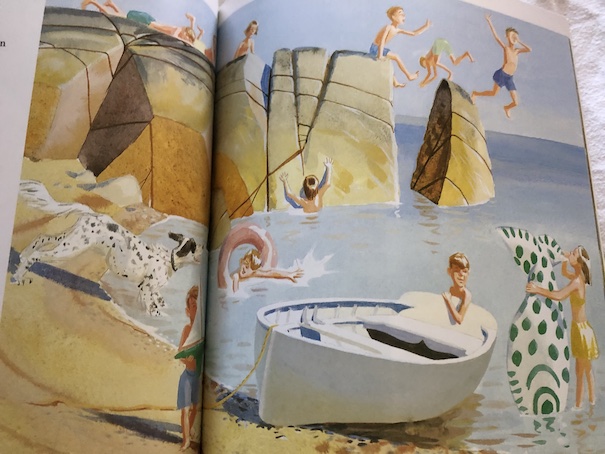

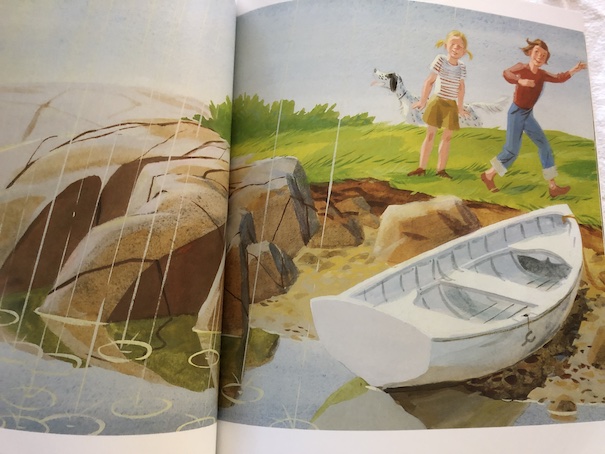

Ian and Sovra Kennedy are brother and sister, and they live by the sea in western Scotland. Their father is the doctor in their small town. One day, after Ian and Sovra have been asking their dad to rent a boat for them so they can explore some of the islands just off the coast where they live, their father tells them that he has bought a boat for them. It’s just a small boat for rowing, but it’s theirs, and it gives them the freedom to explore that they want. There is one island in particular that they want to explore, the one they call Castle Island. Its real name is Eilean Glas, which means “Gray Island”, but they like to call it Castle Island because there’s a square-shaped rock in the middle of the island that looks somewhat like a castle. However, their visit to this particular island has to wait for the end of the book because other events intervene to distract them.

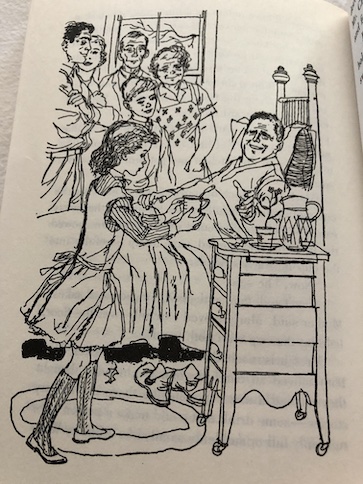

When the children come back from trying out their boat for the first time, they hear their parents arguing about how to accommodate some house guests. Their father’s fishing friend wants to come for a visit. He was going to rent rooms in town for himself, his wife, and their daughter, but the innkeeper has had a stroke and can’t handle guests right now. So, Dr. Kennedy has offered to host the family, but the Kennedy house isn’t very big. If the guests use the children’s rooms, Ian and Sovra will have to camp out in the bothy, which is an old hut in back of the house. Ian and Sovra sometimes camp there anyway for fun, but it does get damp when it rains. Mrs. Kennedy doesn’t like the idea of the children sleeping there if the weather gets bad, but the children think that it sounds like fun and tell their mother that they’ll be fine and that they want to do it.

Dr. Kennedy’s friend is named Tom Paget. Dr. Kennedy doesn’t like Mrs. Paget, although it isn’t completely clear why. All he says about her is that she likes to wear a cloak and paint with water colors, which doesn’t sound very objectionable by itself. (I was actually a little irritated at Dr. Kennedy because he makes repeated comments about how much he doesn’t like Mrs. Paget without offering any more information than that. If she’s just a little eccentric in her style of dress and likes art, so what? I found the parts in the book where they get nitpicky and really down on her irritating.) Their daughter Ann is about the same age as Ian, and because Dr. Kennedy hasn’t yet met her, he’s not sure what she’s like until the family arrives, although he makes a point of saying, to his children, directly, that he hopes Ann isn’t like her mother. (Nope, no further information about why, and Dr. Kennedy sounds rather rude.) Dr. Kennedy’s comments about Ann and her mother leave Ian and Sovra feeling unenthusiastic about their guests, so they plan to spend most of their visit staying out of their way and possibly avoiding Ann, too, if she turns out to be like whatever her mother is like. (Way to go, Dr. Kennedy. Let’s start this whole experience off on a bad foot with everyone primed to hate your house guests, shall we?) Ian thinks that their whole camping outside the house experience would be even more fun if they were further from the house, so they won’t have to deal with the guests poking their noses into the bothy to see where they’re staying or worrying about whether Ann will want to join them because that would be bad for vague reasons.

Ian and Sovra start camping out in the bothy before the guests actually arrive to get things in order. However, they accidentally set fire to the bothy during an accident with their camp fire. With the bothy burned, where are Ian and Sovra going to camp out while the guests use their rooms? Their parents won’t let them have a tent because it won’t be dry enough if it rains. Fortunately, an important discovery that Ian and Sovra make turn this misfortune into an adventure.

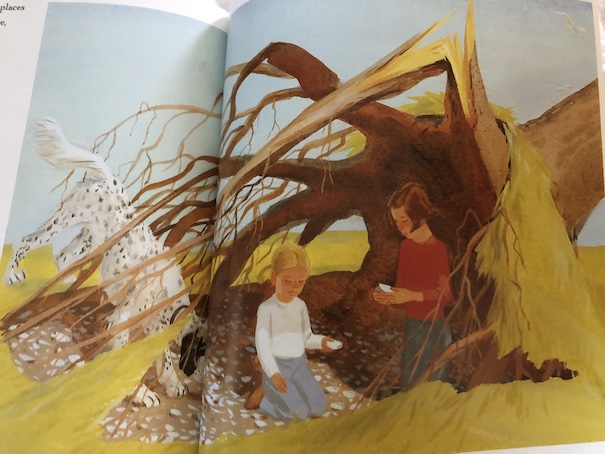

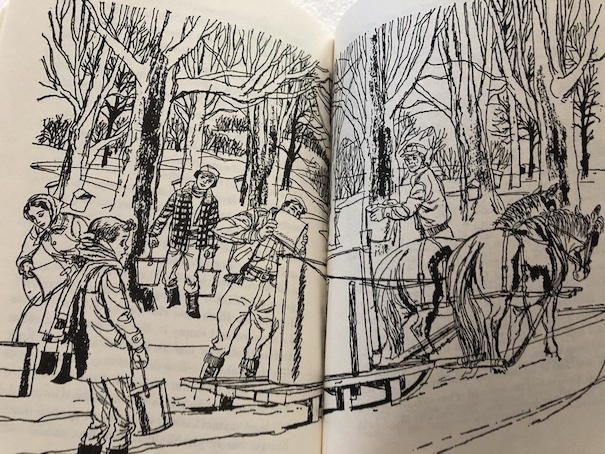

While their parents worry about finding them another place to stay during their guests’ visit, the kids go exploring further in their boat. Their boat gets caught in a whirlpool and is drawn around the back of a waterfall, where they find a hidden cave. More importantly, someone else discovered this cave a long time ago. There are stone steps carved into the rock and a metal ring set into the wall for tying up boats, showing the children that this is an intentional landing spot. When they go up the stone steps, they discover an old, abandoned cottage hidden in a green hollow. (They call it a shieling.) The old cottage is in remarkably good condition for being abandoned for a long time, and Ian thinks that if they clean it up, it would be the perfect place for the two of them to stay during the guests’ visit. Sovra thinks that their parents aren’t likely to agree because the cottage is too far from their own house and rather isolated, and the landing place behind the waterfall is too dangerous. However, Ian is sure that there’s a better landing place somewhere else, if they approach from another side. Upon further exploration, the kids find a collection of cottages that were once a tiny village, older than the shieling they found and abandoned for a long time. The little abandoned village does have a landing place, and they decide that was probably how the people who once lived in the shieling got to where they built their home. They have to be careful, though, because the area is surrounded by a bog that might contain quicksand, and they’re not sure how to get across or around the bog. In the end, they decide that the waterfall entrance is actually the best way to reach the shieling, and they learn to navigate the currents around the waterfall safely.

The children’s father finally gives them permission to camp out in the old shieling, although their mother still has misgivings because the parents aren’t completely clear on exactly where the children will be camping and haven’t seen it yet themselves. The children describe the shieling to their father and tell him that it’s over near Lochhead, another town nearby. Dr. Kennedy is satisfied from their description that the house will be safe to camp in and says that they can communicate with them daily by sending them a message by the postal van from Lochhead, and if they need anything, the parents will send it to them by the same van the next day. Their mother is still uneasy, but since their father is convinced that it will be fine, she finally agrees to let them go. Ian and Sovra are thrilled at having this secret house all to themselves, but Ian says that they will need to keep it a secret and be careful not to leave signs that they’re there, just in case someone still owns the old house and doesn’t want them there, even if they’re not using the house themselves right now.

The children’s discovery and use the shieling is not only the beginning of this story but also the rest of the series. The children’s secret hiding place not only provides them with a secret place of their own but also leads them to some important discoveries about their own family and other people. This book in particular focuses on the missing chieftain of the Gunn clan, who has been presumed dead, but it takes awhile for that mystery to enter the story.

While Ian and Sovra are enjoying their freedom in their secret house, the Pagets arrive with their daughter, Ann. Mrs. Paget turns out to be a somewhat eccentric woman, sometimes overly enthusiastic about little things, raving about them with some cutesy talk. She often elaborates her daughter’s name from Ann (which is what it really is) to the longer Annabel or Annabella (neither of which is her actual name) and referring to the absent Ian and Sovra as the “dear little children.” (Yeah, it’s kind of an annoying cutesiness, but I still think that Dr. Kennedy shouldn’t have been maligning her before she arrived.) Mrs. Paget isn’t just a hobby painter; she has actual shows of her work and has been successful at selling her paintings. When she arrives, she tells the Kennedys that she wants to find the best places in the area to paint, and she’s particularly interested in things like old castles, old bridges, and waterfalls. (I think you can see where this is going.) The Kennedys mention that there are abandoned villages in the area.

Mrs. Paget thinks that sounds exciting and asks about the history of these villages. The Kennedys say that they don’t know the full story behind them, but Donald, the old man they bought the boat from, might know. They think that the people who used to live there probably moved to the bigger cities to find work or something. (This is something that actually did happen to small villages in Scotland in real life. If you’d like to know more about the circumstances and see pictures, I suggest looking at Hirta Island. Although it looks like a pretty spot, living conditions there were harsh, and after a young woman died there who might have been saved if she had lived near a city with a hospital, the people decided that it was too isolated, and they didn’t have the population levels and support they needed to stay there.)

Poor Ann is bored and disappointed by the absence of Ian and Sovra. (Yeah, thanks again, Dr. Kennedy, for all the negative talk that made them not want to even meet poor Ann and be friends with her. In his first message to the children after the guests arrive, Dr. Kennedy makes fun of Mrs. Paget’s sandals, which he says are “made of pink string” and says he doesn’t know why Mrs. Paget wants them to meet Ann. Oh, I don’t know Dr. Kennedy. Let’s all think hard about this. Could it possibly be because Ann is lonely, there are no other kids in the area, and she could use a friend? Why is Dr. Kennedy so mean and weird about this? He’s an adult, for crying out loud! Ian and Sovra think that it would be “frightfulness” if they have to meet Ann and actually “be nice to” her if she’s like her mother. Keep in mind that they still don’t even know what Mrs. Paget is really like because they haven’t met her, and oh, noes, how awful to be nice to somebody who’s a little strange or eccentric during a temporary visit. What a family!) Ann often finds family holidays boring because she’s an only child. When her mother is busy painting and her father is busy fishing, Ann has very little to do and nobody to talk to. Ian and Sovra know that the Pagets have arrived, but they try to avoid meeting them, both because they think that they won’t like the Pagets, not even Ann, and because they want to keep the house where they’re staying a secret.

The very first time Ian sees Ann, he tries to run away from her and ends up falling and getting hurt. Ann tries to help him, although he resists at first, partly because he is afraid that if his mother finds out that he’s hurt, she’ll put an end to the camping trip. Ian messes up Ann’s name, calling her “Animosity,” and I’m not sure if he did it on purpose or because he actually has a head injury from his fall. (Actually, it was probably on purpose because he does it repeatedly from this point on in the story. No, Ian, “animosity” is what your family cultivates for other people and what I’ve been feeling each time your dad criticizes Mrs. Paget behind her back.) Ann messes up Sovra’s name, asking if Ian is saying “Sofa”, but I cut her more slack because Sovra is a more unusual name, and she’s not doing it deliberately. She’s just asking if she heard that right. Ian does explain that although Sovra mostly spells her name “Sovra” for school, her name is really supposed to be the Gaelic word “Sobhrach”, which means “Primrose.” Same name and pronunciation, but different spelling. Ann likes the name for being unusual. Ann goes to get some water for Ian, and while she’s gone, Sovra finds Ian and helps him into their boat. By the time Ann gets back, they’re gone.

Sovra worries about whether Ian has given away their secret to Ann. Ian says he doesn’t think so, but he has been rambling and not thinking straight since he hit his head, so he can’t be sure. He’s dizzy and disoriented and definitely showing signs of having a concussion. He should be checked out by a doctor, who happens to be his dad in this area. However, Sovra takes Ian back to the shieling. Ann worries about where Ian disappeared to, but she realizes that he couldn’t have gone anywhere by himself in his condition, so someone else must have come and helped him. She doesn’t mention what happened when she returns to where her mother is painting by the abandoned village because she doesn’t know where Ian is and can only assume that someone took him somewhere to get help. Both she and her mother spot smoke rising from the hollow where the shieling is, and Ann wonders if that could be Ian and Sovra’s campsite, although she isn’t sure. When Ian and Sovra get another note from their parents, it says nothing about Ian’s injury, so they realize that Ann didn’t tell the adults about it, and they begin to think more highly of her for keeping their secret. (Yeah, as if that was the smartest or most caring thing she could have done. But, these are kid priorities. You’d think with a father who’s a doctor that they’d know better than to be too cavalier about head injuries, though.)

However, soon, there are other things on the kids’ minds. When Ian went to go see Donald about a bung for their boat, he noticed that Donald has a special two-handled cup called a quaich, and his quaich has a symbol on it that’s the same as a symbol that was carved into the hearth of the shieling. Ian and Sovra wonder if that means that Donald actually owns the shieling. When they ask him about it, he tells them that the symbol is a juniper sprig and it’s the badge of the Gunn clan. Donald questions them about why they want to know, and they carefully say that they’ve seen the symbol carved somewhere else. Donald realizes what they’re talking about, and he tells them that he once helped to build the little house where they’re staying. Years ago, his cousins lived in the little abandoned village, and he found that secret cave behind the waterfall himself when he was young. He’s the one who created the secret landing place and stone steps. The Gunns once owned the village and the land around it, but the head of the family, Colonel Gunn, died without children. Since then, Kindrachill House, the bigger house where Colonel Gunn lived, has been empty. Colonel Gunn did have a nephew named Alastair, but everyone believes that he died somewhere in the Far East. Alastair used to live in the shieling where Ian and Sovra have been staying. Donald gives the kids permission to continue staying there, since it seems that the original owner isn’t coming back. He also tells them that there’s a superstition in the Gunn family that, when Kindrachill House is empty, the heir to the estate will not arrive until someone lights a fire in the hearth. Ian wonders if they really have to light a fire only in the hearth at Kindrachill to make the legend come true or if it would count that they’ve been lighting fires in the hearth at the shieling, where Alastair used to live and where he carved his family’s crest in the hearth. Sovra says that it doesn’t really matter since Alastair’s dead and can’t come back … but is that really true?

When things in the shieling are moved around when Ian and Sovra aren’t there, they assume that Ann has found their hideout. They know that she’s been looking for it. Later, she admits to them that she has been there, having figured out a way to get there that Ian and Sovra don’t even know about, but she didn’t move all of the things that have been moved. Someone else who knows about the shieling has been there. They know it’s not Donald because he has trouble walking and can’t make the trip to the shieling by himself. So, who else could it be?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction and Spoilers

The location of the story gives it an almost timeless quality. The children spend much of their time in nature, with few references to modern technology, so the story could take place in many time periods. However, the book is set contemporary to the time when it was written, in the mid-20th century, after WWII. That time period is especially important in the third book in the series. This first book in the series could take place during many possible decades, but the third book can only be set during the 1950s because WWII is important to that story.

There is a slight element of mystery to the story, but the kids aren’t actively trying to solve the mystery element. Mostly, it’s a kind of adventure story with elements of slice-of-life about how these kids spend their summer in an exciting location with a somewhat mysterious history. Little pieces of the situation are gradually revealed to the characters during their adventures. Kids like stories about other kids who have adventures without adult supervision, and parts of the story are about the fun things they do, setting up house in the old cottage and enjoying themselves in and around the secret hideaway.

The Kennedys’ Attitude Problems

I have to say that I didn’t like the attitudes of any of the Kennedys. I actually read the third book before this one, and I liked the characters better in that book. In this book, both the parents and the kids seem to be some kind of snobs. They’re negative and mean about Mrs. Paget and her daughter for little reason. Granted, I don’t like cutesiness much, but Mrs. Paget just seems to be a mildly eccentric artist who dresses a little oddly and acts overly enthusiastic about some things. I didn’t think there was any call for a medical man like Dr. Kennedy, who should be at least somewhat understanding about human nature because of his profession, to be so mean about the way Mrs. Paget dresses or try to discourage his children from being nice to Ann. There’s almost a mean girl exclusiveness quality to the Kennedys’ behavior. Most of the men I know have little knowledge about women’s clothes, but Dr. Kennedy sounds like a middle school mean girl, nitpicking the way the poor woman dresses. He even writes about it in the notes that he sends to his kids during their camping trip. The pink rope sandals bother him so much that he wants to put that in writing to his kids who aren’t even there and who should be polite to this guest when they actually meet. Dude, you live a “simple” life in a cottage near a small town on the coast of Scotland. You’re not exactly in a high society fashion district, and there are few people around to see or care what anybody dresses like. So what if she likes to wear cloaks with sandals? It’s an odd clothing choice because it seems to indicate that she’s dressing for two different types of weather at once, but it’s harmless. Calling the landscape “delicious” and the children “dear little children” (“dear” seems overly generous to me, but Mrs. Paget doesn’t know any better) might seems a little sappy, but again, so what if she’s somewhat sappy and romantic in her speech? Calling her daughter Ann by much longer names which she could have just named her in the beginning, like Annabel or Annabella, is also a little odd, but if Ann doesn’t seem to care, why should anybody else? Families do sometimes have odd nicknames for kids, and it’s not the worst I’ve ever heard. Going from a shorter name to a longer one is the opposite of what most nicknames do, but again, it’s just harmless eccentricity. None of the things Mrs. Paget does seem really that bad. Mrs. Paget doesn’t do anything rude or mean, and she seems like a pretty unobtrusive guest. Mostly, she just wants to find pretty spots where she can sit most of the day and work on her paintings while her husband fishes, so if they don’t like her cute, sappy talk, they don’t have to hear it much. She only seems to return to the Kennedy house to eat and sleep, and that’s literally the least a host can provide a house guest.

The Kennedys are fine in the scenes when they’re just by themselves, but when their guests are around, they’re barely holding back inner meanness and rudeness for the guests that seems completely undeserved. That was a constant source of tension for me while reading the book. When Mrs. Paget is asking about beautiful spots in the area with enthusiasm and interest in their history, Dr. Kennedy is thinking about the best way to answer her questions quickly so he can just talk to her husband (about fishing, I guess), like he just wants her to shut up. The men are going to go off fishing together, during which they’ll have hours to talk about anything they want, and Dr. Kennedy thinks it’s such an imposition to talk to Mrs. Paget for a few minutes when they first arrive about the area where he lives and its history, for which Mrs. Paget has only expressed admiration and interest. Mrs. Kennedy also seems oddly defensive to Mrs. Paget about the “simple” life they lead, which she seems to think is too simple for Mrs. Paget, but Mrs. Paget reassures her that isn’t the case, that she thinks the area is charming and the children’s camping trip sounds like fun. Mrs. Paget seems overly enthusiastic about how great it all is. Whether she’s really that enthusiastic on the inside, I couldn’t say, but at least she speaks positively and makes an effort to show interest. She is definitely interested in the artistic possibilities of the area and sincerely curious about its history. She follows up her curiosity by asking Donald about what he knows, which shows effort.

Meanwhile, the Kennedys are trying to hide their negativity, which seems to spring from ideas they have about Mrs. Paget that aren’t born out in real life. There’s little indication of how the Kennedys got these ideas except their own inner negativity and insecurity. When I was a kid, my mother would tell me to be nice to other people and to make visitors feel welcome, and even if I wasn’t having fun with particular visitors, to remember that their visit was only temporary and make the best of it until it’s over. You can feel any way you want, but you still have to behave yourself. Being nice to a temporary guest is not a terrible imposition, and putting up with a less-than-ideal guest is completely bearable and encourages return hospitality. The Kennedys don’t impart these lessons to their children, and the father seems to particularly discourage this thinking. This is the type of family that breeds little bullies, people who think that generally being nice to people is a terrible burden to endure. It really struck me as pretty rotten for Dr. Kennedy, a grown man in a position of trust and responsibility for the welfare of people in their community, to try to discourage his children from meeting and being nice to Ann, a lonely child who never did anything to Dr. Kennedy and doesn’t deserve this bad treatment from him, smearing her reputation and making it difficult for her to make friends. Why is Dr. Kennedy trying to get his kids to be mean to Ann instead of telling them to be kind to a guest and make friends?

Of course, I really know why the Kennedys have to be this way. It’s a plot device. Their reasons for not liking Ann and her mother don’t have to be fair or make complete sense because it’s the results that matter. It’s all to set up part of the conflict of the story. If Dr. Kennedy was nicer about Mrs. Paget and encouraged his kids to be nice to Ann, they wouldn’t be so worried about having Ann around or joining them on their camping trip. Ian wouldn’t have been so worried about Ann seeing him that he tried to run from her, fell, and got that concussion. If the kids were friendlier with each other, Ann wouldn’t have needed to get a ride from a stranger or might have told them about the man she met who gave her a ride and who turns out to be important. Quite a lot of the problems the kids encounter would have been different or simplified if characters were nice with each other and worked together more. It’s a theme that appears often in literature, and actually, quite a lot in real life, too. It doesn’t make it any less annoying for me.

Character Development

The parts where I thought Ian and Sovra were at their best were when they were completely by themselves. They seem to have a good brother-and-sister relationship and know how to function as a team. Even when one of them messes something up and they criticize each other, they still have each other’s back and work together to clean up their messes. However, I never really got to like Ian and Sovra as people during this book because of their meanness and snobbishness, which is ironic because they later say that they don’t like Ann because she thinks that she’s better than they are. This seems to be a retroactive decision by the author because she doesn’t show that trait right away. It seems to surface later in the story, long after Ian and Sovra have decided that they don’t like Ann and need to avoid her and think it would be frightful to be nice to her.

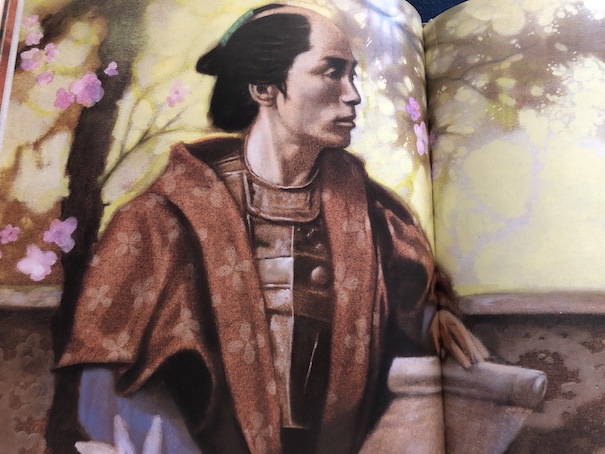

My favorite characters in the story are thoughtful Ann and kind Alastair. Yes, Alastair does appear in the story. He’s not dead. Ann is the first to meet Alastair on his arrival back in the area, and he helps her when Ian and Sovra have been mean to her, stealing her shoes so she can’t follow them back to their secret house from the beach and leaving her to limp back to the Kennedy house over rocks with a hurt foot. Ann vents to Alastair about her troubles with the Kennedys without knowing who he really is, and he tells her that he’s sorry that she’s having such a bad time and that the Kennedys have been unpleasant to her. Finally, a voice of reason and compassion in the story! Ann doesn’t mention this encounter with Alastair to anybody at first because she doesn’t know who he is, that they all think he’s dead, or that his return has any special meaning.

Little by little, Ian and Sovra do start to feel guilty about the way they’ve treated Ann and start looking at her differently, noticing the things she does well and acknowledging some of the skills and knowledge she has. Eventually, Sovra does apologize to Ann for stealing her shoes. When Ann is seasick the first time they take her out in their boat, she admits that she’s not as used to sailing as they are, which makes her seem less superior than Ian and Sovra thought she was. Ann even apologizes for talking like she knows everything when she doesn’t, but I still thought it was weird because that wasn’t the impression that I was getting from her until after Sovra and Ian started saying that’s what she was doing. The apologies they each give each other and their mutual acknowledgement of each other’s faults and strengths help them come to a better understanding of each other and resolve their conflicts.

Ann also proves to Ian and Sovra that she does know things that even they don’t know about the shieling and the area around it because of the questions her mother asked Donald about the history of the area. Donald told Mrs. Paget that there was once a pathway between the abandoned village and the shieling that was lost years ago, apparently swallowed up by the bog, and nobody knows quite where it is now. However, this summer has been drier than normal in the area, and Ann realizes that the path might have been exposed again by the lower water levels in the bog. She carefully observes the area from a high vantage point when they go hiking in the mountains until she spots where the path goes and marks it on her map. Then, the next time her mother goes to the village to paint, she scouts for the beginning of the path from the ground, finding a series of stepping stones through the bog.

When Ian and Sovra ask her later how she got to the shieling when she didn’t know about the waterfall entrance, she explains to them what she did, and they ask her to show them where the path is. I liked this part because Ian and Sovra were smug earlier about Ann’s map, saying that they didn’t need any local maps like that because everyone knows where everything around here is anyway, and their big source of pride with Ann was that they know more about the area than she does. (They thought that her explanations of what’s on her map when they asked her to show it to them earlier was just her trying to be “superior” to them.) They do know a lot from living there for their whole lives, but the problem is that they count too much on that sometimes and don’t think to ask the questions Ann and her mother do because Ann and her mother are aware of what they don’t know and are actively trying to learn.

I also liked it that when Ian and Sovra finally let Ann join them camping at the shieling, they also let her take over the cooking. Earlier, they took exception to her father saying that she’s an excellent cook because they saw it as bragging and acting superior, but Ann really is good at cooking and likes doing it, and Sovra admits that she isn’t terribly good at it and doesn’t really like it herself. I was relieved when the characters stopped worrying about who was superior to who and who was acting superior when they shouldn’t and just let people do what they’re good at and interested in doing, acknowledging when someone does something well without adding a kind of put-down onto it, like Ian and Sovra did earlier.

Alistair

Getting back to Alastair’s return, he eventually shows up at the shieling and talks to the children, explaining what happened to him. He says that he tried to talk to them before, but they weren’t at the shieling the last time he stopped by. His plane was wrecked in the Pacific (They don’t say that it happened during the war, so it might not have been. I thought they might have been implying that he was a pilot in the war, but that would play with the timing of later books in the series.), as they heard, and he spent some time living with a native group on an island. The natives were friendly enough and helped him, but it took him awhile to learn enough of their language to really communicate with them and figure out how to get to a place where he could arrange passage home. That was when he first learned that he’d been declared dead. Since then, he’s been reestablishing his identity and checking on the estate that he’s inherited. By the time that Alastair finally shows up at the shieling and introduces himself to the children, they’ve heard that Kindrachill House is supposed to be sold to pay the mortgage. When they ask Alastair about it, he confirms that he doesn’t have the money he needs to pay the mortgage. He almost didn’t come back to the area at all because he didn’t think there was anything there for him. However, it turns out that he’s an art lover, and when he went to a showing of Mrs. Paget’s paintings in Glasgow, he saw the painting she did of the old village and how she included the smoke rising from the shieling where Ian and Sovra were staying. That made him want to return to his old cottage and see who was there. So, the legend about a fire in the hearth bringing the Gunn heir home comes true.

There is an argument among the four of them whether Ian and Sovra should get the credit for Alastair’s return because they lit the fire in the hearth at the shieling or whether Mrs. Paget should get the credit because her painting is what drew it to Alastair’s attention, but it’s a good-natured debate. There is still the problem of the mortgage that needs to be paid, but Ian, Sovra, and Alastair find the solution to the problem when they finally go take a look at Castle Island, and Ann rescues them when they accidentally maroon themselves there. Since Ian was the first to spot the solution to their problem, Alastair thanks him by giving him the shieling so he and his sister can use it whenever they want. Alastair is able to save Kindrachill House and takes up his role as chieftain of the Gunn clan, which sets up the other stories that follow in this series.

My Favorite Parts

The best parts of the book for me were its timeless quality and the location. A secret house, forgotten by everyone, accessed by going behind a waterfall and climbing a hidden stone stairway is just the sort of place I would have loved as a kid. Even as an adult, I love the idea of a secret hideaway in a picturesque spot. The location and atmosphere are what I recommend to other readers the most. The imagery of the setting is wonderful, and it’s a great place to escape to mentally, if you can’t get to such a spot physically.

I also like books that bring up interesting facts and bits of folklore for discussion. At one point in the book, Ian explains singing sand to Sovra, which is dry sand that makes a sound when people walk on it under the right conditions. (This YouTube video demonstrates what singing sand can sound like on Prince Edward Island.) A less pleasant but still informative part is when Sovra breaks the necks of the fish they catch to kill them quickly. I’m not sure if I’ve heard of other people doing that when they fish or not. It makes sense when they explain it, but I know very little about fishing. I’ve never lived near bodies of water and haven’t gone fishing, and I get squeamish about things, so I’ve never asked.

On a day of heavy mists, Ian and Sovra are also fascinated with how muffled and mysterious the land looks and talk about how it probably inspired stories they’ve heard about ghosts and “second sight” and doppelgangers (although they say it as “doublegangers”). Ian explains how doppelgangers are like “the wraith of someone who’s still alive, so there are two of them.” This piece of folklore is why we refer to people who bear a strong resemblance to each other without being actual twins as doppelgangers. (Some people also call them “twin strangers.”)