Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster, 1912.

Seventeen-year-old Jerusha Abbott has spent her entire life at the John Greer Home for orphans. She has no memory of her parents and no experience of life outside the orphanage. Usually, when an orphan has not been adopted and has finished his or her education at the basic level provided by the orphanage, which does not always include high school, the orphanage and its trustees arrange for the child to be placed in a job so he or she can begin earning a living. Jerusha Abbott has stayed longer than most. She is bright and finished her studies early, so she was allowed to attend the local high school, helping out with some of the younger children at the orphanage to help earn her keep. However, now that she is about to graduate from high school, the orphanage and trustees have been trying to decide what to do with her. After the most recent meeting of the trustees, the matron of the orphanage calls Jerusha into her office to tell her what they have decided.

Jerusha has done well in high school, and her teachers have given her excellent reports. In particular, Jerusha has excelled in English class. One of her essays for English class, entitled “Blue Wednesday,” is a humorous piece about the difficulties Jerusha has preparing the young orphans in her charge for the monthly visits of the trustees: getting them nicely dressed, combing their hair, wiping runny noses, and trying to make sure that they all behave nicely and politely to the trustees. Jerusha hadn’t expected the matron or the trustees to ever read it. The matron thought that the essay was too flippant and showed ingratitude toward the orphanage that raised her, but one of the trustees in particular appreciated the quality of writing and the humor of the piece. This particular trustee is one of the wealthiest, although he usually prefers to remain anonymous about his donations and uses the alias “John Smith.” “John Smith” has helped some of the boys leaving the orphanage by funding their college educations, but so far, he has not done the same for any of the girls, not apparently thinking much of girls or their continued education. Jerusha Abbott and her essay cause him to change his mind. He thinks that Jerusha Abbott could make a great writer, and he is willing to fund her college education. Although the matron thinks that he’s being overly generous with Jerusha, this benefactor has arranged to pay for her college tuition and boarding at an all-girls college and will even provide her with a regular allowance like the other students at college will have from their parents. In return, he still wants to remain anonymous and doesn’t want to be embarrassed with too much thanks, but he does insist that Jerusha write monthly letters to him, updating him about her progress in school and what is happening in her daily life. Not only is he interested in her progress, but he also thinks that the letters will provide her with good writing experience.

Most of the book, aside from the early part that explains about Jerusha’s past and how she is able to attend college, is in the form of Jerusha’s letters to her mysterious benefactor. (This is called epistolary style.) They cover her entire college education, from her arrival at the campus to her graduation and what happens after. The letters in the book are only Jerusha’s, with no replies from her benefactor shown because her benefactor does not write to her until almost the end, only sending money and an occasional present (like flowers, when she was sick).

In spite of the matron’s instructions to keep her letters basic and to show proper respect and gratitude, Jerusha’s lively personality comes through and is often a bit irreverent, just the style that her benefactor prefers. In her first letter, she describes her very first train ride to the college and how big and bewildering the college campus is to her. She also confides the matron’s final instructions to her about how she should behave for the whole rest of her life, including the part about being “Very Respectful.” She says that she finds it difficult to be Very Respectful to someone who goes by the alias of “John Smith.” It bothers her that it’s so impersonal. She’s been thinking a lot about who “John Smith” really is and what he’s really like. She has never had a family, and no one has ever taken any particular interest in her before, and now she feels like her benefactor is her family. She tells him that all she knows about him is that he is rich, that he is tall (from a brief glimpse she had of him as he was leaving the orphanage), and that he doesn’t like girls (from what the matron told her). Based on these qualities, she chooses the one that yields the best nickname, that he is tall and has long legs, and gives him the more personal nickname of “Daddy-Long-Legs.” All of her letters to him from this point forward are addressed with this nickname. At one point, she says that she hopes that the comments she makes about her previous life at the orphanage don’t offend him, but she knows that he has the advantage of being able to stop paying her tuition and allowance if he decides that she’s too impertinent. That knowledge doesn’t stop her from making occasional jokes or flippant comments about life at the orphanage.

Jerusha loves college and begins making new friends, particularly a girl who lives in the same dorm, Sallie McBride. Sallie is very friendly, and but her roommate, Julia Rutledge Pendleton, is more stuffy and standoffish. Julia comes from a very wealthy family, one of the oldest in New York. Julia doesn’t notice Jerusha right away. She is too wrapped up in her family’s prestige, and she seems to be bored by everything going on around her. By contrast, Jerusha is excited by everything because everything is a new experience to her. Sallie gets homesick, but Jerusha doesn’t because she doesn’t have a regular home to miss. For the first time, she gets new clothes, not hand-me-downs or not the standard gingham that the orphans wear. Jerusha also gets a room to herself, for the first time in her life. Jerusha realizes that she can be completely alone whenever she wants to and spend time getting to know herself without other people.

One of Jerusha’s first moves to get to know herself and establish her personal identity is to change her name to Judy. Jerusha was a foundling who came to the orphanage without a name and was named by the matron. Jerusha knows that the matron chooses children’s last names from the phone book, and she picked Abbott for her right off the first page. The first names that the matron gives are random, and she happened to notice the name “Jerusha” on a tombstone once. Jerusha has never liked her name, and she thinks that “Judy” sounds like a girl “without any cares,” which is the kind of girl she would like to be and wishes she was. She is also pleased and amazed when her teachers praise her creativity and originality because, at the orphanage, the 97 children who lived there were dressed and trained to behave as if they were 97 identical twins instead of 97 individuals. Creativity and nonconformity were not generally encouraged.

One of the most difficult and embarrassing parts of college for Jerusha/Judy is that the other girls there know many things that she does not because the orphanage never thought it was important to teach her those things. Most of them are cultural references, like who Michelangelo was or that Henry VIII was married multiple times. (That part actually surprises me. Jerusha did attend a public high school, and my high school covered these subjects. We also read some of the books that Jerusha says that she never read, and we are told that she did well in English class. It makes me wonder if, by “English,” they mean that the class focused only on writing the English language and did not study literature at all.) At the orphanage, Jerusha was never introduced to the childhood classics that the other girls know, like Mother Goose rhymes, fairy tales like Cinderella, or stories like Alice in Wonderland or Little Women. She has not read any of the popular novels or classics like those by Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, or Rudyard Kipling. Before she came to college, she didn’t even know who Sherlock Holmes was. Sometimes, when the girls make jokes about certain things in popular culture, Judy doesn’t understand, and she can tell that people notice when she misses the point of the discussion or doesn’t get the joke. Sometimes, she feels like she’s visiting a foreign country where people speak a language she doesn’t understand. Some people may say that studying things like art, history, and literature are not important, but there are benefits to understanding history and a shared culture, and Jerusha feels the lack of that in her life.

Jerusha/Judy is afraid to tell the others that she grew up in an orphanage because she doesn’t want to seem too strange to them. Instead, she just says that her parents are dead and that a kind gentleman is helping her with her education. Later, when Julia begins to take an interest in her and to press her for details about her family, Judy makes up a name for her mother’s maiden name because she doesn’t want to have to explain her past to Julia while Julia brags about her own pedigree. One of the reasons why Judy doesn’t show much gratitude toward the people who raised her at the orphanage and its trustees is because she has been raised differently from other children. The orphanage fed, clothed, and educated her in a basic way, but their care for her was minimal. She wasn’t really loved there, and in some ways, they have not adequately prepared her for the outside world. Outside of the orphanage, she feels like something of an oddity and just wants to be like the other girls.

At one point, a local bishop visits the college and gives a speech, saying that the poor will always be with us and the reason that there will always be poor people is to encourage people to be charitable. Although Judy can’t say anything, she gets angry at the speech because it implies that poor girls like her are basically like “useful domestic animals,” that they exist for no other reason than to be of use to other people to improve their character by enabling them to be charitable to someone lesser than themselves. Judy wants to be thought of as her own person, someone who is deserving of the good things in life because she is a person, not just someone who serves a purpose for someone else to show off their largesse. The fact that she feels comfortable enough to let even her benefactor, who is giving her largesse, know how she feels about these things shows how deeply Judy feels these issues and how much she needs someone to understand her feelings. Since no one else knows about Judy’s background, she feels compelled to tell her benefactor what she can’t tell others. Judy is grateful for her benefactor’s help and generosity, enabling her to attend college, but her gratitude has limits. At no point does the money she receives change her personality, her personal feelings about poverty, or her feelings about her benefactor himself. Judy knows that the benefactor’s generosity will end with her graduation, and she is mindful that, from that point on, she will be expected to be her own person, make her own way, and manage her own life.

At various points in the book, Judy becomes philosophical and discusses serious issues and the way that she sees life, offering her views and remarks on topics like socialism, the vanity and burden of fashion (yet the need women have to consider it and how it can make a difference in a woman’s life and attitude), the concept of wealth and the narrower topic of personal finances and debts, family lineage and what it can mean for individuals, self-determination and personal freedom, education and culture, and toward the end of the story, romance and marriage. When Judy meets her benefactor (without knowing at first that he is her benefactor) and gets to know him, she finds that they have similar attitudes about many of these topics, although there are times when he tries to tell her what to do and she rejects his orders, acting on her own initiative. As I said before, Judy is aware, increasingly so throughout the book, that she is her own person, and while she is grateful for her benefactor’s help, she has limits on that gratitude, feeling that there are some things that her benefactor has no right to insist on. Her independence grows particularly toward the end of the book, when Judy must seriously consider her life after graduation, when she expects that her benefactor’s generosity will end. One of the purposes of a college education is to expose students to new ideas and experiences, opening new channels of thought and giving them the chance to establish their identities and views on particular subjects. For Judy, everything is a new experience, but she learns quickly and establishes definite views and her own strong personality.

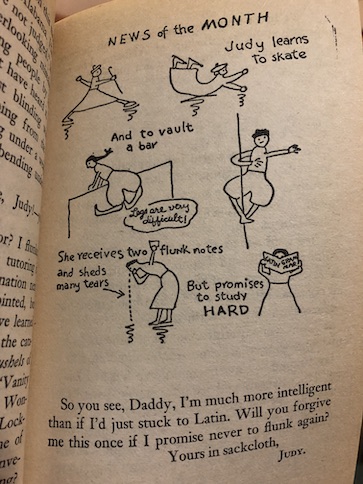

Judy’s letters are full of humor and are often accompanied by little sketches of her activities. She discusses her classes and her joy at being accepted on the girls’ basketball team. (There were women’s and girls’ basketball teams back in the early 1900s and 1910s, when this book was written. These pictures show what their uniforms looked like.) She catches up on all the books that she has missed reading before, and she loves reading them. The more she reads, the more she understands what the other girls are talking about when they mention their childhood favorites or make jokes about the things they’ve read. When Judy reports what she’s studying in her classes, she often does so in a creative way, like when she describes Hannibal’s battle against the army of Ancient Rome as though she were a war correspondent. She does very well in English and gym classes, but fails her Latin and mathematics courses and needs tutoring.

Over Christmas, Judy stays at the school with a fellow student named Leonora. They treat themselves to a lobster dinner at a restaurant, Judy buys herself a few presents with the Christmas money sent by her benefactor, and they have a molasses candy pull (people used to make that kind of taffy candy at parties with other people) with some other students.

Gradually, Judy begins being more friendly with Julia, even though she still thinks that Julia is a snob, and she becomes friendly with Julia’s uncle, Jervis Pendleton, who comes to visit the college. Jervis is Julia’s father’s youngest brother, a handsome, wealthy, and good-natured man. He is very kind to Judy when they meet, and he later sends Julia, Sallie, and Judy some candy. His age is never given, but Judy comments in one of her letters that she imagines that he is much like her benefactor would have been 20 years earlier, believing her benefactor to be a much older man, although she has not been told his age.

When it’s time for her first summer holidays, Judy actually tells her benefactor that she cannot face going back to the John Grier Home and would rather die than go back for the summer, even though the matron has written to say that she will take her if she has nowhere else to go. Judy loves being free from the orphanage and can’t stand the idea of going back and being pressed into service to take care of the younger children again. Instead, her benefactor arranges for her to spend the summer at a farm owned by Mr. and Mrs. Semple in Connecticut. The Semples tell her that the farm used to belong to Jervis Pendleton and that Mrs. Semple was his nurse when he was a child. He gave the farm to her out of fondness for her. If you haven’t guessed already, this is an important clue to the identity of Judy’s mysterious benefactor.

Recounting all of Judy’s adventures during the rest of her college education would take too long, but she does become roommates with both Julia and Sallie during her sophomore year. This gives Judy more opportunities to see Julia’s Uncle Jervis. She visits Sallie’s family at Christmas, getting a taste of happy family life, and she meets her brother, Jimmie. Jimmie seems fond of Judy, but Judy’s mysterious benefactor doesn’t allow her to spend the summer with the McBride family, where she would be going to dances with him and his college friend. Instead, he insists that she go to the farm in Connecticut again, so she is there when Jervis Pendleton drops in for a visit. (Another important clue.) Judy does disobey her benefactor’s orders and gets a job and goes to see Jimmie the following summer instead of going on a trip to Europe that he had originally arranged for her.

Judy also furthers her writing ambitions, winning a writing contest and sending stories and poems that she writes to magazines, eventually selling some and writing a novel that will be published in volumes. She is a published author by the time she graduates from college.

At the end of the book, Judy’s benefactor reveals his true identity, which Judy had not guessed, only after Judy reveals her feelings regarding him in her letters. Initially, before she knows the identity of her benefactor, she turns down the offer of marriage he makes to her in person, but as she reveals in her letters to Daddy-Long-Legs, the reason is that she thinks that he knows nothing about her past, and she doubts that a wealthy man like him would marry a poor orphan if he knew. The book ends with Judy’s letter to her benefactor/fiance after she goes to meet him at his home and he tells her the truth. When she realizes that he does know all about her past and has loved her all along for the person she really is through her letters and his periodic visits, she agrees to marry him.

This book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive. The book has been adapted for stage and screen many times over and in different countries around the world. There is also a sequel called Dear Enemy, which focuses on Sallie McBride and what she does after graduating from college.

My Reaction and Spoilers:

I realized that I couldn’t give my full opinion about the book without revealing the identity of Judy’s benefactor, although probably most people would have guessed it already. Judy’s benefactor throughout the book is Jervis Pendleton, Julia’s uncle. I’ve read other reviews of the book where people find the romance between Judy and Jervis to be somewhat creepy, both because of the difference in their ages and because of the benefactor relationship between them. It is a relationships of two people who are not equals, and that can create some awkwardness, but I don’t think that it’s quite as bad as some reviewers suggest for several reasons.

As I said, Jervis’s age is never given in the book. Judy is in her late teens in the beginning of the story, and by the end of her college education, she is in her early 20s. Judy is old enough to get engaged and married by the end of the book, so it’s not a case of an adult taking advantage of a minor. From the descriptions of Jervis, the fact that he is older and more mature than Jimmie, and Judy’s estimate on meeting him for the first time that he is like how she imagines her benefactor might have been 20 years before (because she imagines her benefactor as a middle-aged or older man), my guess is that he is probably somewhere in his 30s. He could be as young as late 20s, a few years out of college, but I’m inclined to think that he’s older because he is very well-established in life and has apparently been making donations to the orphanage for at least several years. He could be as old as his 40s, but I’m thinking that he’s probably younger than that because he is supposed to be much younger than Julia’s father, and I think that Julia’s father is probably in his 40s, based on her age. It makes sense to me if Jervis is in his 30s, perhaps 10 to 15 years older than Judy. It’s a significant age gap, but not as creepy as a 50-year-old man being interested in a 20-year-old girl. From the descriptions given, Jervis is definitely older than Judy but not old enough to be her father.

Some people in other reviews wondered if Jervis was specifically grooming her to be his wife from the very beginning by funding her education, which would be creepy, but I don’t think that’s the case. Jervis is supposed to be something of an eccentric, which is why he doesn’t seem particularly close to the rest of his family, like Julia. He is given to acting on whims, and since the matron at the orphanage said that he’s never shown any particular interest in the female orphans before, I don’t think he’s the kind of man who is attracted to young girls in a creepy way. I think all that the story was trying to portray was that Jervis, as an eccentric, just really enjoyed Jerusha’s essay in the beginning, that it appealed to his odd sense of humor, and since he was there to bestow a donation on the orphanage anyway, decided to make Jerusha the beneficiary of his donation because the oddity of the situation appealed to him. People don’t usually fall in love on first acquaintance, so I doubt that he started thinking about that just by reading a funny school essay. More likely, that idea evolved later. My guess is that he thought that the whole thing was funny at first, paying her way through college while occasionally showing up as Julia’s uncle, maintaining his secret identity as “Daddy-Long-Legs.” It probably started out as a kind of game for a rich eccentric, but it turned into something more serious along the way, as he really got to know Judy. Judy’s letters are humorous, but they also have their serious side, and they discuss some very serious subjects. As I said, Judy and Jervis discover that they actually have some similar attitudes about a number of serious things in life, and that is one of the factors in a good, long-term relationship.

Because their relationship is one of unequals, particularly early in the story, there could be the concern that Judy might feel obligated to agree with Jervis and even love him out of gratitude, but Judy’s irreverent attitude and belief that gratitude has limits make that less of a concern. Jervis is older than Judy and definitely richer, but he doesn’t always call the shots in her life, even though he sometimes tries. Judy resents when he tries to keep her from associating with Jimmie (presumably, Jervis had started developing some romantic feelings toward her at that point and was trying to separate her from a rival), and she actively defies his orders when she refuses to go on a trip to Europe her benefactor had arranged and gets a job instead. Remember that Judy was not expecting her benefactor to support her after college. Getting a job and establishing friendships and romantic relationships in her life were perfectly natural steps for a person preparing herself for an independent life. Judy sees these things as being more practical to her future than a trip to Europe, which is actually reasonable. Jervis was disappointed, but I think that he probably had to acknowledge, partly through Judy’s explanations in her letters and some internal reflection that we don’t get to see because we never hear his thoughts in the story, that Judy is being reasonable, especially because at that point, she doesn’t know his real identity or how he is beginning to feel about her. I think Judy’s acts of defiance also help to make her more of an equal to Jervis by the end of the book, although not completely because he is still older and richer. What puts Judy on a better footing with Jervis is that she has come to realize the benefits of her education and that she is now her own person. She doesn’t have to marry Jervis because of his money because she is starting to establish her own life. She has become a published writer and has had independent employment experience, and there are young men who find her interesting. She could have chosen to pursue Jimmie instead, but at that point, she really didn’t want to. Choosing Jervis was a real choice for her because she did have other options, and when she made that choice, she was unaware of his status as her benefactor, making that not a factor in her choice.

One other thing that I’d like to mention is that, at no point in the story, does Judy ever discover her parents’ true identities. When I read a book that features an orphan with an unknown past, I often find myself wondering who her parents are and if that backstory will be revealed in the course of the story. In this book, it is not revealed, and Judy never expects that it will be. She has always lived at the orphanage, and at her age, she has no expectations that her parents will suddenly come looking for her. She feels the absence of family and relatives in her life because it makes her different from other people, and she wants someone close to her to confide in, but she has no expectations of meeting any blood relatives. She makes no attempt to find them and doesn’t spend much time speculating about who they are. Jervis has no more idea who Judy’s parents are than Judy does, and it doesn’t matter to him. In the end, the story isn’t about what Judy came from or who her family was but about the person that Judy becomes.

4 thoughts on “Daddy-Long-Legs”