Mystery of the Inca Cave by Lilla M. Waltch, 1968.

Thirteen-year-old Richard Granville has been living in Peru for the last two years. His family moved from California to a mining town in the Andes because his father is a manager for a mining company. Richard enjoys living in Peru because he’s developed an interest in archaeology and the history of the Incan civilization. Richard feels like the mountains are a connection to the distant past, and he loves the historical feel of the place. His parents don’t understand how he feels and would rather see him work harder at his schoolwork instead of spending all of his time exploring the mountains. Richard’s father tells him that he won’t become an archaeologist if he doesn’t apply himself to his studies, and his mother worries that something could happen to him in the mountains. They think he should finish school first and then decide if he wants to go into archaeology or not, but Richard’s mind is already made up, and he doesn’t want to waste this golden opportunity to do what he loves most right now. Richard feels hurt that his parents don’t really listen to him, don’t share his interests, and don’t appreciate the finds he’s already made.

Richard loves to explore the area with his friend, Todd Reilly, and see if they can find pieces of Incan relics. They’ve found some interesting bits of pottery and broken tools, but one day, they make a particularly exciting discovery – an ancient stone road mostly covered with grass. Although Richard knows that there are many other remains of Incan roads, this one is particularly tantalizing because it seems more hidden than most. Richard is fascinated with how neatly the stones of the road fit together so precisely without mortar, and he wonders where the road leads.

The boys explore the old road further, but they discover that at least part of the road was buried in a landslide. Todd doubts that they’ll ever be able to find where the road leads, but Richard wants to keep trying. When they return to the spot to try again, Richard spots the remains of an ancient building! Richard is sure that the building was once a chasqui station (also called tambos), which was a place where Incan messengers could stop, rest, and trade off with other messengers, who would continue to carry messages along the route, like the members of the Pony Express used to trade off with each other. Richard knows that stations like that were placed about 2.5 miles apart along roads, so there might be other stations located along this route.

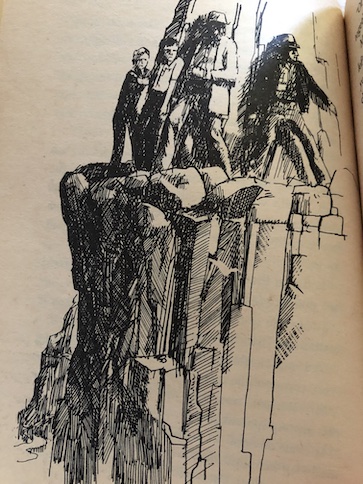

The boys go a little further and find a stairway leading up the side of a cliff to a cave. On the stairs, Richard finds a small doll. The doll is puzzling because Richard isn’t sure if it’s an Incan relic that somehow managed to survive or if it’s a more modern doll made by the South American Indians in the area. He has trouble believing that any more modern person could have been at this spot recently because it’s pretty isolated and rough territory. It looks like other landslides could happen. He can’t tell his parents about his discovery because they probably wouldn’t let him return to the area to explore it further if they knew how dangerous it was, and he can’t bring himself to abandon the most exciting discovery he’s ever made.

On a trip to the marketplace, Richard and Todd spot a mine foreman, Jeb Harbison, yelling at a boy in Quechua. He stops as soon as he sees the other boys watching, and they wonder what that was about. Then, the boys spot a merchant selling dolls that are similar to the one they found at the ruins. They ask the merchant where the dolls came from and who made them, and he gives them the name of the doll maker, a woman named Deza. Todd thinks that the most likely explanation for the doll they found is that some young girl living in the area got a doll from the same doll maker, and she lost it while playing around the cave. However, Richard doesn’t think that’s likely because the cave is such an out-of-the-way place, not somewhere a young child could easily reach alone.

On another visit to the area of their discovery, the boys find a mine shaft that doesn’t belong to the company their fathers work for, even though it’s on land that they know the company owns. There are signs that someone is actively mining there, but who?

The boys also discover that the activity at the cave is connected to the mine when they see some men there, breaking up rocks and stuffing them inside of little dolls, like the one they found earlier. It seems like the miners are smuggling gold or other minerals in the dolls, but when the boys talk to Richard’s dad about what they’ve seen, the situation points to a possibly larger conspiracy.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive. The book was originally titled Cave of the Incas.

My Reaction

The first thing that I liked about this book was the pieces of information about the ancient Incas. Our knowledge of ancient civilizations has increased since the 1960s, but the information in this book is still good. I liked the book’s descriptions of Inca building techniques, how they used closely-fitted stones instead of mortar, and how their system of messengers was organized. There are also points where the characters notice parallels between the way the ancient Incas lived and the way their descendants live, such as their system of cooperative farming.

However, this story is also about human relationships as well as adventure, mystery, and ancient civilizations. Through most of the book, Richard is troubled about his relationship with his parents, especially his father. His parents are frustrated with him because he is absorbed by his interest in archaeology and exploring the countryside and isn’t applying himself to his schoolwork. At the same time, Richard hates it that his parents don’t understand what interests him and only seem to want him to focus on what they want. They’re having a clash of priorities.

When I was a kid, I hated homework with a vengeance. That might be a surprising revelation about an adult who willingly does what are essentially book reports on a regular basis as a hobby. Reading is fun. Research produces interesting information. I like knowing things and writing to other people about them. Basically, I was always good at the skills necessary for homework, so that wasn’t the problem. The problem is that there were many other things I wanted to do, and homework got in the way. I didn’t always get to read about what I wanted to read about in school because someone else was always choosing the school material for me, and I frequently hated their choices. Even the arts and crafts weren’t always the ones I wanted to learn, and I was usually told what to make instead of getting to make what I wanted. Because I was a good student, I ended up in the honors classes, so I always had more homework to do than everyone else. I was proud that I was a good student, but at the same time, I also hated it because I found it stifling. I’ve always been interested in many different subjects and handicrafts, but all through my childhood, I felt like I could never just take up all the different projects I wanted to do because I had to do my never-ending supply of homework first. Everything I wanted to do always had to wait. Even after I graduated, it was difficult for me to shake off the feeling that I had to wait on things I wanted to do , which was also kind of irritating.

I could sympathize with Richard’s attitude toward his own studies. He knows what he really wants to do, and he finds it infuriating that his parents want him to put it off and finish his homework and his education first. There is something to be said for making the most of finding himself in the very place he wants to be with direct access to what he knows he wants to study seriously. The move to Peru was an enriching experience for Richard that gave him a direction and life ambition, and I think he would regret it forever if he didn’t use this opportunity to explore it as much as possible. At the same time, though, my adult self knows that there is truth to what Richard’s parents say about his explorations in the mountains. The mountains are dangerous, like Richard’s mother says, and even Richard knows it. Also, Richard’s father is correct that if Richard seriously wants to be a professional archaeologist, he’s going to have to finish his education.

Nobody in modern times becomes a serious, professional archaeologist without a college degree, and even archaeologists need to study things beyond their specialist field. Archaeology isn’t just wandering around, digging, and seeing what you find. You have to recognize what you find, study its context, understand its significance, and know how to treat it to preserve it. You can’t study past lives and interpret artifacts without having real life and world knowledge. Archaeology is also where science and history intersect. Archaeologists need to know mathematics, geology, and how humans are affected by climate (which can and does change over time, for various reasons) and access to resources. There are legal and ethical principles to archaeology that Richard will also have to understand. Archaeologists can also benefit from learning drawing and photography to record and interpret finds and perfecting their writing skills to present their findings to the world. Richard has made a good start in his field of interest, but to get serious about it, he will need more education and greater depth and breadth of knowledge.

As annoying and stifling as homework feels, the skills it imparts are necessary for doing many more interesting things. Getting through the studying phase can be a pain, but sometimes, you really have to lay a solid foundation before you can build something solid on it. I still think that my past school assignments could have been more interesting and less stressful if I’d had more flexibility about them and more time for personal projects in between. However, I have realized over the years that, once you’ve really learned something, you will use it, even if you only use it indirectly as part of something else. I don’t regret learning the things I learned because, as hard as it was along the way, I have used things I learned in more interesting ways later in life. I’ve also realized that, if I had spent less time and emotions complaining about how stifling my homework situations were, I also could have used the time I spent lamenting about homework and procrastinating about it to accomplish some of the other things that I complained that I never had enough time to do. Not all of them, but more than I did when I was too busy being upset and resentful about homework. That’s also a lesson that Richard learns in the story.

At one point, Richard talks to Todd about his relationship with his own father, and Todd says that they get along pretty well. Richard realizes that Todd and his father don’t fight over his studies because Todd is an easy-going type who doesn’t mind doing his homework much and takes care of things without making anybody nag him to do it. Todd just accepts that there are some things that just need to be done, so he doesn’t waste time complaining or procrastinating about them. That’s harder for Richard because he feels the strong pull of what he really wants to do.

Todd admits that he and his parents don’t always get along perfectly because he doesn’t always do what he’s supposed to do. There are times when he leaves messes or physically fights with his brother or talks back to his mother, and his parents get angry or irritated about it. When Richard asks Todd what he does in those instances, Todd says that, eventually, after the initial argument, he typically apologizes or cleans up his mess or does whatever he needs to do to fix the situation. Todd’s reasoning is that, while people aren’t perfect and don’t always do what they should, “when you’re wrong, you’re wrong.” He accepts that, sometimes, he screws up and needs to do something to fix it without getting too overwrought about having been in the wrong. He sees it as just a normal part of life. When it happens, he can correct himself and move past it.

In the case of Richard and his father, each of them has to admit to being a little wrong and accept that the other is partly right. Both of them have to do some work to fix their relationship. Richard has to admit to his father that he does need to continue his education and apply himself to getting his work done. In return, his father needs to try harder to understand Richard’s interest in archaeology and allow him some time and opportunities to make the most of his time in Peru, getting the firsthand knowledge and experience he needs for the future he really wants and that won’t come from the standard classes he’s taking.

Through their adventures in the course of the story, Richard and his father come to a better understanding of each other and have an honest conversation about how to manage the conflicts in their relationship. Richard’s father admits that he needs to stop looking at his son as being just a younger version of himself and to see Richard for the independent person he is, with his own interests and goals in life. Meanwhile, Richard connects somewhat to his father’s interests through their investigation of the illegal mining operation he and Todd discovered.

This mystery story is a little unusual for children’s books, where kids often investigate mysteries on their own, having adventures without the adults, because Richard’s father joins the boys in their investigations and he stands up for them and what they’ve discovered when their discovery is challenged. The shared adventure becomes a bonding experience for Richard and his dad. At the end of the story, Richard’s father helps Richard connect with a museum curator, who helps the whole family to see the true value and significance of Richard’s archaeological finds. The curator also emphasizes to Richard that, while he has the potential to excel in his chosen field, he’s going to have to study and move on to higher education to get where he wants to go. Richard agrees, now having a greater understanding of its importance and satisfied that his parents understand the direction he’s chosen for his life.