The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, 1961.

Milo is a boy who never really knows what he wants or what to do with himself. He is always bored because he doesn’t really know the purpose or point of doing anything. Nothing he learns in school interests him because he can’t see what he could ever do with the knowledge. He never bothers to read the books he has, play with his toys, or learn to use his tools because he just doesn’t have the imagination to appreciate them or what he could do with them.

One day, when Milo gets home from school, he finds an unexpected package. It’s not his birthday or Christmas, but the package is definitely intended for him because it has his name on it: “For Milo, who has plenty of time.” There is a list of items contained in the package: 1 tollbooth (which must be assembled, according to the directions), 3 precautionary signs (“to be used in a precautionary fashion”), some coins for the tollbooth, a map (with no familiar places on it), and a driver’s rule book (which must be obeyed). Interestingly, it promises that if Milo is not satisfied with his tollbooth experience, his time will be refunded. Since Milo doesn’t think he has anything else to do anyway, he decides that he might as well unwrap the tollbooth and set it up.

Although Milo thinks that the map is purely fictional and that the tollbooth is just a playset, he decides that he might as well select a destination on it for his trip through the tollbooth. He closes his eyes, puts a finger on the map, and selects a place called “Dictionopolis.” He gets in the toy car, puts a coin in the tollbooth, and goes through it.

To his surprise, Milo suddenly finds himself driving down a real highway, no longer in his own apartment. He sees a sign pointing the way to a place called Expectations, and he stops to ask a man about it. At first, he thinks he’s talking to a weather man, but the man corrects him, saying that he’s really the “Whether man.” Part of his job is to hurry people along, even if they have no expectations. Nothing the Whether Man says to Milo makes sense to him, so he decides that he’d better just get going.

As Milo drives down the highway, he gets bored and starts daydreaming. As his mind wanders, the scenery gets duller and grayer, the car slows down, and eventually, the car stops and won’t move further. Milo looks around and wonders where he is. It turns out that he’s in the Doldrums, the home of the Lethargarians. They tell him that thinking isn’t allowed there. Milo says that’s a dumb rule because everybody thinks. The Lethargarians say that they never think and Milo must not have thought either because, if he had, he wouldn’t be there. People usually get to the Doldrums because they’re not thinking, and once they’re there, nobody is allowed to think. They refer Milo to the rule book that came with the tollbooth. Milo looks in the rule book and sees that is a rule. There are also limits on laughing and smiling in the Doldrums. Milo asks the Lethargarians what they do if they can’t think or laugh. They say that they can do anything as long as they’re also doing nothing. Mainly, they do things like daydreaming, napping, loafing, loitering, and wasting time. They say it gives them a full schedule and allows them to get nothing done, which they consider an important accomplishment. Milo asks them if that’s what everybody here does, and they say that the one person who doesn’t is the Watch Dog, who tries to make sure that nobody wastes time.

At that point, the Watch Dog shows up. The Watch Dog looks like a dog, but his body is an alarm clock. The Watch Dog asks Milo what he’s doing, and is alarmed when Milo says that he’s “killing time.” It’s bad enough when people waste time, but killing it is horrible! (The book is full of these kinds of puns. It’s just getting started.) Milo explains how he got stuck in the Doldrums while he was on his way to Dictionopolis and asks the Watch Dog for help. The Watch Dog explains that if he got there by not thinking, he can also get out by thinking and asks to come along because he likes car rides. Milo agrees, and the two of them get in the car. Milo thinks as hard as he can (which the book notes isn’t easy for Milo because he’s not used to thinking and doesn’t do it too often). Gradually, as Milo thinks of various things, the car begins to move. The faster Milo thinks, the faster the car goes. Milo learns that it’s possible to accomplish a lot with just a little thought.

The Watch Dog’s name is Tock because his older brother is named Tick. However, their names are a mistake because his older brother only makes a tock sound, and Tock only makes a tick sound. It’s a source of pain and disappointment. Tock tells Milo about the origin of time and why Watch Dogs find it important to make sure that people use time well. He says that time is the most valuable possession because it always keeps moving.

When they arrive at Dictionopolis, the gatekeeper won’t let them in immediately because Milo doesn’t have a reason for being there. Nobody gets let in without a reason. Fortunately, the gatekeeper always keeps a few spare reasons lying around, and he decides to let Milo have one. The one he selects is “WHY NOT?”, which the gatekeeper considers a good, all-purpose reason for doing anything. (I don’t know. I’ve heard that one followed up by an angry “I’ll tell you why not!” before.)

As readers have probably guessed, Dictionopolis is all about words. When Milo enters the city, he finds himself in the marketplace, which is called the “Word Market.” The ruler of Dictionopolis is Azaz the Unabridged, and when Milo is welcomed to the city by the members of the king’s cabinet, they do so in multiple ways, using synonyms. Milo asks them why they don’t just pick one word and stick with it, but they’re not interested in that. They say that it’s not their business to make sense and that one word is as good as another, so why not use them all? (That isn’t true, but the story tells you why not later.) They go on to tell Milo that letters grow on trees here, and people come from all over to buy all the words they need in the Word Market in town. Part of the cabinet’s duty is to make sure that all of the words being sold are real words and have real meanings because people would have no use for nonsense words that don’t mean anything and that nobody will understand. The cabinet doesn’t seem to care about whether or not the words are being used in a way that makes sense as long as they’re real words. (If you’re familiar with business speak or buzzwords, you’ve probably noticed that much of it works on a similar principle.) Putting the words into a context that makes sense isn’t their job. (Later, you meet the person who had that job.) However, the cabinet does advise Milo to be careful when choosing his words and to say only what he means to say. They excuse themselves to get ready for the banquet and say that they’ll see Milo there later, although Milo doesn’t know what banquet they’re talking about.

Milo and Tock explore the Word Market. Milo is fascinated by the variety of words available. He doesn’t know what they all mean, but he thinks that if he can buy some, he can learn how to use them. He chooses three words he doesn’t know: quagmire, flabbergast, and upholstery. (I’m surprised he didn’t know the last one because, surely, he has upholstered furniture in his apartment.) Unfortunately, Milo quickly realizes that he has only one coin with him, and he’ll need that coin to get back through the tollbooth. Eventually, he finds a stall selling individual letters for people who like to make their own words. The stall owner gives them some free samples to taste. They taste good to Milo, and the stall owner tells them that sets of letters come with instructions. Milo doesn’t think he’s very good at making words, but the Spelling Bee, a giant bee, begins showing him how to spell words. However, the Humbug, a grumpy bug, tries to tell Milo not to bother learning. The Spelling Bee tells Milo not to listen to the Humbug because he just tells tall stories and doesn’t actually know anything, not even how to spell his own name.

The Spelling Bee and the Humbug start fighting and knock over all the word stalls around them. There is a big mess, all the words get scrambled, and it takes some time before everyone sorts everything out. By that time, the Spelling Bee is gone, and when the policeman comes, the Humbug blames everything on Milo and Tock. At first, it seems like Milo will get off lightly because the policeman (who is also the judge) gives him the shortest “sentence” he can think of (“I am”). Unfortunately, he’s also the jailer and takes Milo and Tock to prison for 6 million years.

In the prison, Milo and Tock meet the Which. At first, Milo thinks that she’s a “witch”, but she says many people make that mistake. The Which is King Azaz’s great-aunt, and her job used to be to make sure that people correctly chose which words to use and didn’t use more words than necessary. (A problem that Milo noticed in the market.) The Which explains that she was thrown into prison because she got too carried away with her job and became too miserly with words. Word economy is good (and something I struggle with), but rather than promoting brevity, the Which started promoting silence instead,. It got so bad that people eventually stopped buying words and the market was failing, so the king had to put a stop to it. The Which says that she understands now where she went wrong, and Milo asks her if there’s anything that he can do to help her. The Which says that the only thing that would help her would be the return of Rhyme and Reason. When Milo asks who they are, she tells him the story of the founding of the Kingdom of Wisdom.

Years ago, the King of Wisdom had two sons, and he was proud of both, but one of them had an obsession with words, and the other had an obsession with numbers. The king didn’t realize how bad their conflict was growing, and it got worse over time. One day, the king found a pair of abandoned infant twins. The twins were both girls, and the king had always wanted daughters as well as sons, so he adopted them and named them Rhyme and Reason. Everyone loved Rhyme and Reason, and they had a talent for resolving problems and disputes. When the king died, he left his kingdom to both of his sons and left instructions for them both to look after Rhyme and Reason. The word-obsessed son, Azaz, established a capital city of his own, Dictionopolis, and the number-obsessed son, the Mathemagician, established the city of Digitopolis. Rhyme and Reason remained in the city of Wisdom and acted as advisers to the brothers, mediating their disputes. This system worked until the brothers got into their worst fight over whether words or numbers are most important. They took this dispute to Rhyme and Reason, who said that both are of equal importance. This satisfied most people, but both brothers were angry because they had wanted the girls to make a definite choice between them. In their last joint act, they banished Rhyme and Reason to the Castle in the Air. Since then, there has been continued fighting between the two brothers and their respective cities, the city of Wisdom has been neglected, and there’s been no Rhyme or Reason to any of it. (Ha, ha.)

Milo says that maybe they could rescue Rhyme and Reason from the Castle in the Air. The Which says that would be difficult because there’s only one stairway to the castle, and it’s guarded by demons. Milo remembers that there is also the matter of them being stuck in prison for 6 million years. The Which says that being in prison isn’t really a problem. Although the policeman/judge/jailer likes putting people in prison, he doesn’t care much about keeping them there, so Milo and Tock can leave when they like, and he probably won’t notice. (Sounds like he’s not very good at the “jailer” part of his job.) The Which points out a button on the wall, Milo presses it, and a door opens.

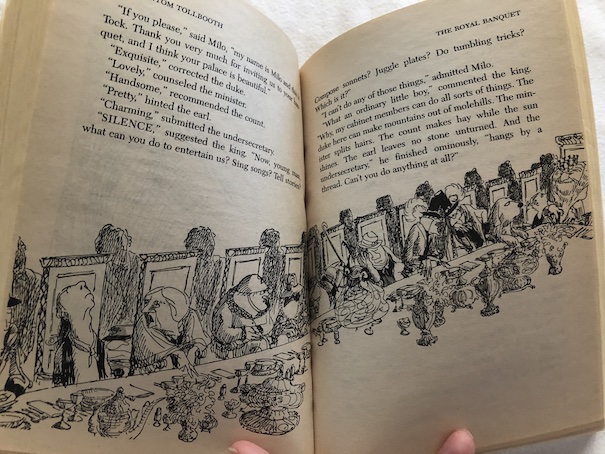

When they step outside, the king’s cabinet members come to take him to the banquet that they mentioned earlier. They have Milo and Tock step into their wagon and tell them to be quiet because “it goes without saying.” (Ha, ha.) They take Milo and Tock to a palace shaped like a book, where they meet King Azaz and join the banquet.

The banquet is a pun-filled meal where everyone has to literally eat their words and have half-baked ideas for dessert. (Half-baked ideas look good, but you shouldn’t have too many because you can get sick of them. Tock says so.) Nothing makes sense, and even the king realizes it, which gives Milo the opportunity to suggest bringing back Rhyme and Reason. The king isn’t sure that’s possible, and the Humbug, of course, volunteers Milo and Tock for the job. The joke turns out to be on him because the king volunteers the Humbug to assist Milo. Reaching Rhyme and Reason will be a perilous journey, and possibly the most difficult part will be getting the Mathemagician to agree to let them do it.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies). There is also a movie version of this book (mostly animated but part live action) with songs. You can see a trailer for it on YouTube.

My Reaction

The Phantom Tollbooth is a fantasy story, but like many fantasy stories, it’s also a morality story. It’s a little like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which aims to correct children’s bad habits. Milo’s boredom problems are due to his lack of thought for the things he could do and imagination to figure out how to make use of what he has. His adventures after he goes through the Phantom Tollbooth help him to see things differently and to learn to use his mind creatively.

However, I wouldn’t say that the story is too preachy. A couple of parts started to feel a little like a lecture, but it’s set in a fantasy land that feels a little like Alice in Wonderland. There’s a healthy dose of nonsense that keeps things interesting and fun. The book is peppered with puns and peopled by a fascinating variety of characters. There’s the boy who can see through everyone and everything, who teaches Milo to look at things from an adult perspective and helps him to realize the benefit of keeping his feet on the ground (both of those are also puns). There’s the man who is the world’s shortest giant, the world’s tallest midget, the world’s thinnest fat man, and the world’s fattest thin man all at the same time. Basically, he’s just an ordinary guy who’s noticed that people think of him in different ways when they compare him with themselves.

I was first introduced to this story when I was in elementary school, as many people were. Our teacher read it to us and showed us the cartoon version. Parts of songs from that version still get stuck in my head, almost 30 years later. (“Don’t Say There’s Nothing To Do the Doldrums …”) The part of the story that stuck with me the longest was the Dodecahedron, a shape with twelve sides. If you’ve seen the twelve-sided dice used for Dungeons and Dragons and similar role-playing games, those are dodecahedrons. In the book, the Dodecahedron is talking character as well as a shape, but I remember it because our teacher gave us paper cut-outs to make our own dodecahedrons. I made two of them, and I might still have one somewhere.