The Story of Ruby Bridges by Robert Coles, illustrated by George Ford, 1995.

This is a beautifully illustrated picture book about Ruby Bridges, one of the first black children to attend a school that was formerly all-white during the desegregation of schools that took place during the Civil Rights Movement. The story is told in the form of the memories of Ruby and other people, looking back on their experiences, rather than as a first-person account.

When the book begins, it introduces Ruby as the child of a poor family who moved to the city after her father lost his job picking crops when farmers began using mechanical pickers instead. After her family moved to New Orleans in 1957, her father worked as a janitor, and her mother became a cleaner at a bank.

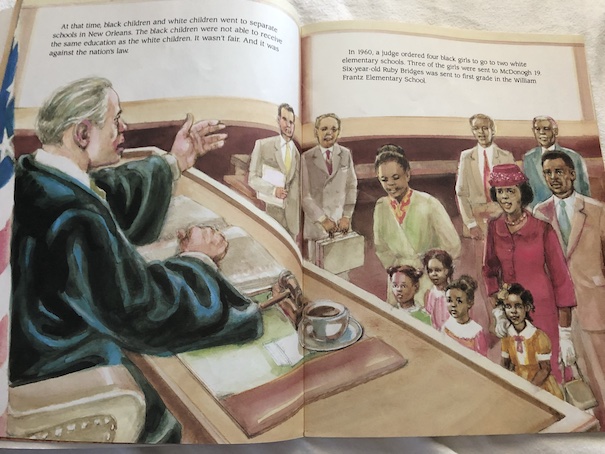

The book explains briefly that schools were segregated at the time, and that black children were not given an education that was equal to what was offered in white schools. Because the book is for children, it doesn’t go deep into detail about the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation or exactly how Ruby Bridges’s family became involved. (Ruby was selected as one of the children because she passed a test for academic aptitude, showing that she could keep up with a class of white children, who had better early education.) It simply says that, in 1960, a judge decided that four young black girls would be sent to schools that had been for just white children and that six-year-old Ruby Bridges was one of them.

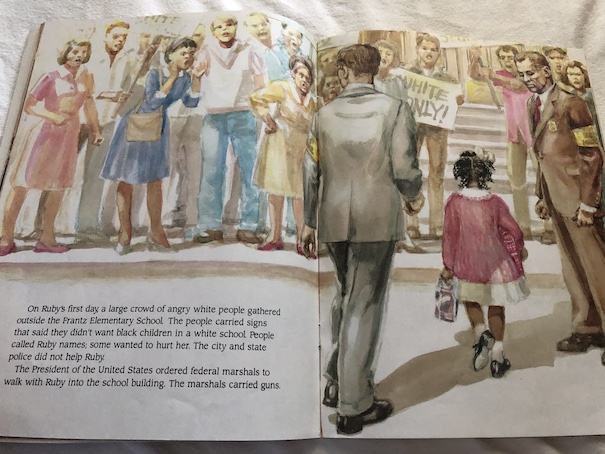

It was a harrowing experience for young Ruby. There were protesters outside the school, yelling angrily and threatening the little girl. For her safety, she had to be escorted by armed federal marshals.

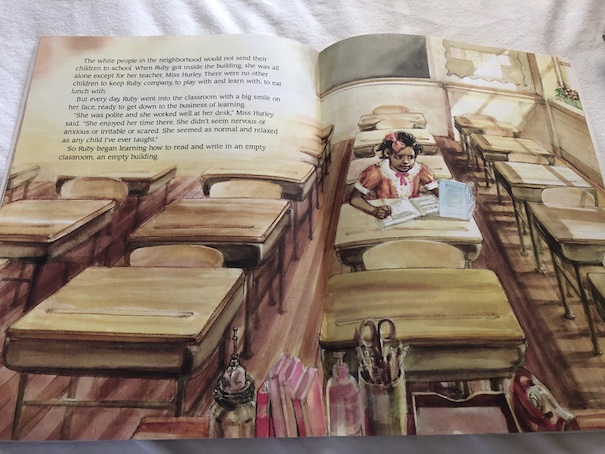

Parents in the area refused to send their children to school so they wouldn’t be in the same classroom with a black child, so Ruby Bridges was literally in a class all by herself. Her teacher, Miss Hurley taught Ruby in an otherwise empty classroom. Miss Hurley was surprised at how Ruby was able to keep a good attitude in spite of the angry protestors and the lack of other children.

One day, Miss Hurley was looking out the window as Ruby approached the school, and she thought she saw Ruby saying something to the angry crowd before coming inside. When Miss Hurley asked Ruby what she said to them, Ruby said that she was talking to them; she was praying for them. Miss Hurley hadn’t realized it before, but Ruby had a ritual of praying for the people who were angry and hated her every day before school. This was just the first time that Miss Hurley had seen her doing it.

Ruby also said the same prayer after school. This prayer was part of what helped her get through those difficult days of hostility and loneliness.

The book ends by explaining that the parents soon began to send their children to school again and let them join Ruby’s class because they realized that life had to continue and that keeping their children from their education was hurting them. The angry protestors gradually gave up. Ruby continued going to school and eventually graduated from high school. She later married a building contractor and had four sons of her own. She founded the Ruby Bridges Educational Foundation to help parents become more involved with their children’s education and to promote equality in education.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

I’ve heard the story before of Ruby Bridges praying for the people threatening her and protesting against her. This particular rendition is very good, although there is one thing that confuses me. According to this book, her teacher’s name is Miss Hurley, but I understood her name was Barbara Henry. I thought perhaps Hurley was her maiden name and that she later got married, but I haven’t been able to find anything to confirm that. I haven’t found anything to explain where the name Hurley came from at all. I’m not the only reviewer who questions the name confusion.

Ruby Bridges wrote books herself about her experiences, at different reading levels, and they’re also available on Internet Archive.